WIC

Participation

and

Pregnancy

Outcomes:

Massachusetts

Statewide

Evaluation

Project

MILTON

KOTELCHUCK,

PHD,

MPH,

JANET

B.

SCHWARTZ,

MS,

RD,

MARLENE

T.

ANDERKA,

MPH,

AND

KARL

S.

FINISON,

MA

Abstract:

The

effects

of

WIC

prenatal

participation

were

exam-

ined

using

data

from

the

Massachusetts

Birth

and

Death

Registry.

The

birth

outcomes

of

4,126

pregnant

women

who

participated

in

the

WIC

program

and

gave

birth

in

1978

were

compared

to

those

of

4,126

women

individually

matched

on

maternal

age,

race,

parity,

education,

and

marital

status

who

did

not

participate

in

WIC.

WIC

prenatal

participants

are

at

greater

demographic

risk

for

poor

pregnancy

outcomes

compare

to

all

women

in

the

same

community.

WIC

participation

is

associated

with

improved

pregnancy

outcomes,

including,

a

decrease

in

low

birthweight

(LBW)

incidence

(6.9

per

cent

vs

8.7

per

cent)

and

neonatal

mortality

(12

vs

35

deaths),

an

Introduction

Efforts

to

improve

the

health

status

of

pregnant

women

and

their

young

children

through

nutritional

supplementa-

tion

and

education

have

long

been

a

part

of

public

health

programs

in

the

United

States.

The

Special

Supplemental

Food

Program

for

Women,

Infants

and

Children

(WIC),

established

in

1972,

is

the

largest

and

most

specifically

targeted

public

health

nutrition

program

in

the

United

States

today.

The

WIC

program

is

designed

to

reach

high-risk

pregnant

and

lactating

women,

infants,

and

children

up

to

5

years

of

age

with

supplemental

foods

and

nutrition

educa-

tion,

as

an

adjunct

to

good

health

care.'

WIC

is

the

first

federal

nutrition

program

to

use

identifi-

able

nutritional

risk,

in

addition

to

low

income,

as

a

criterion

for

eligibility.

Since

its

inception,

WIC

has

grown

to

provide

benefits

to

2.9

million

persons

monthly,

at

a

cost

of

$1.36

billion

in

fiscal

year

1983.

An

estimated

500,000

pregnant

women

now

participate

in

the

WIC

program.

Eligible

participants

receive

a

monthly

set

of

food

vouchers

redeemable

at

local

grocers

for

specific

foods

tailored

to

individual

needs.

Allowable

foods

include:

milk,

cheese,

iron-fortified

cereal,

100%

fruit

juices,

eggs,

dried

beans,

peanut

butter,

and

iron-fortified

formula

for

infants.

The

cost

of

the

food

package

is

approximately

$30

per

month,

provided

at

no

cost

to

the

participants.

Nutrition

education

is

also

provided.

A

more

complete

description

of

the

WIC

program

appears

elsewhere.2

The

WIC

program,

despite

its

magnitude

and

its

clearly

stated

public

health

goals,

has

not

been

extensively

exam-

ined.

The

lack

of

research

may

be

the

result

of

a

moral

acceptance

of

the

virtues

of

feeding

high-risk

women

or

of

the

methodological

difficulties

of

conducting

quality

re-

search

in

a

large,

decentralized

nutrition

program.

The

latter

include

the

difficulty

of

obtaining

a

proper

comparison

sample,

the

lack

of

data

collected

uniformly

across

program

sites,

and

the

need

for

large

sample

sizes

to

show

stable

From

the

Division

of

Family

Health

Services,

Massachusetts

Department

of

Public

Health.

Address

reprint

requests

to

Milton

Kotelchuck,

PhD,

MPH,

Department

of

Social

Medicine

and

Health

Policy,

Harvard

Medical

School,

25

Shattuck

Street,

Boston,

MA

02115.

This

paper,

submitted

to

the

Journal

June

27,

1983,

was

revised

and

accepted

for

publication

March

21,

1984.

Editor's

Note:

See

also

Different

Views,

pp

1145-1149

this

issue.

C

1984

American

Journal

of

Public

Health

0090-0036/84

$1.50

increase

in

gestational

age

(40.0

vs

39.7

weeks),

and

a

reduction

in

inadequate

prenatal

care

(3.8

per

cent

vs

7.0

per

cent).

Stratification

by

demographic

subpopulations

indicates

that

subpopulations

at

higher

risk

(teenage,

unmarried,

and

Hispanic

origin

women)

have

more

enhanced

pregnancy

outcomes

associated

with

WIC

participa-

tion.

Stratification

by

duration

of

participation

indicates

that

in-

creased

participation

is

associated

with

enhanced

pregnancy

out-

comes.

While

these

findings

suggest

that

birth

outcome

differences

are

a

function

of

WIC

participation,

other

factors

which

might

distinguish

between

the

two

groups

could

also

serve

as

the

basis

for

alternative

explanations.

(Am

J

Public

Health

1984;

74:1086-1092.)

program

effects.

To

date,

only

two

evaluations

of

prenatal

participation

in

WIC

based

on

perinatal

outcomes

have

been

published.

Despite

quite

divergent

methodologies,

Edozien,

et

al,3

and

Kennedy,

et

al,4

both

reported

that

WIC

partici-

pation

is

positively

associated

with

maternal

weight

gain,

infant

birthweight,

and

gestational

age,

and

that

the

WIC

programs'

effectiveness

is

enhanced

by

increasing

duration

of

participation.

Others

maintain

that

the

value

of

WIC

is

unproven.5

This

paper

reports

the

results

of

the

Massachusetts

WIC

Statewide

Evaluation

Project,

which

examined

the

associa-

tion

between

maternal

participation

in

the

WIC

Program

in

1978

and

the

outcomes

of

pregnancy.

Specifically,

four

questions

were

addressed:

*

Does

the

WIC

Program

reach

its

target

population?

*

Is

WIC

participation

associated

with

more

positive

outcomes

of

pregnancy?

*

Are

the

effects

of

WIC

participation

similar

across

all

high-risk

subpopulations?

*

Are

the

effects

of

the

WIC

program

enhanced

with

increased

duration

of

participation?

The

Massachusetts

WIC

Program

The

Massachusetts

WIC

program

is

similar

to

WIC

programs

nationally.

In

1978,

it

operated

through

23

non-

profit

local

health

centers

and

social

service

agencies

under

contract

with

the

State

Department

of

Public

Health.

Ap-

proximately

22,000

persons

participated

monthly,

of

whom

over

4,000

were

pregnant

women.

At

the

time

of

the

study,

geographic

eligibility,

in

addition

to

income

guidelines

and

nutritional

risk,

was

a

criterion

for

WIC

participation.

In

Massachusetts,

the

issuance

and

redemption

of

all

WIC

food

vouchers

is

centrally

monitored

through

a

single

computerized

bank

control

system.

This

system

allows

for

an

accurate

documentation

of

the

names,

duration

of

partici-

pation,

and

number

of

vouchers

redeemed

for

all

prenatal

WIC

participants.

Methodology

Study

Population

The

basic

design

of

the

study

is

a

direct

comparison

of

the

pregnancy

outcomes

of

two

groups

of

Massachusetts

women

who

gave

birth

in

1978:

those

who

participated

in

the

WIC

prenatal

program,

and

a

matched

control

group

of

non-

WIC

women.

The

derivation

of

the

study

population

and

AJPH

October

1984,

Vol.

74,

No.

10

1086

WIC

PARTICIPATION,

PREGNANCY

OUTCOME:

MASSACHUSETTS

TABLE

1-Selected

Maternal

Demographic

Characteristics,

1978:

WIC

Participants,

Catchment

Area

Resi-

dents

and

All

Massachusetts

Residents

%

WIC

%

Catchment

%

All

Massachusetts

%

WIC

Saturation

Characteristics

Participants

Area

Residents

Residents

of

Catchment

Area

Age

s17

years

12.2

6.0

3.8

36.4

l19

years

28.6

16.9

11.5

30.4

Education

-9

years

14.9

10.5

5.1

25.4

<12

years

49.2

31.5

19.0

28.0

Mantal

Status

Unmarried

40.7

23.9

13.7

30.6

Married

59.3

76.1

86.3

14.0

Race

Black

23.8

16.0

6.2

27.0

White

73.6 81.6

91.8

16.2

Parity

1

44.9 45.9

44.6

17.6

5+

6.5

4.1

3.3

28.4

TOTAL

(N)

(4,126)

(22,995)

(67,187)

study

data

results

from

the

linkage

of

two

computerized

data

systems:

the

WIC

bank

voucher

system,

and

the

State

Birth

and

Death

Registry.

Appendix

A

summarizes

the

three

steps

were

involved.*

First,

the

names

of

all

women

who

registered

as

a

WIC

prenatal

participant

were

drawn

from

the

WIC

computerized

participant

voucher

reports

(N

=

4,898).

Data

on

the

dura-

tion

and

number

of

vouchers

cashed

per

month

were

also

extracted.

Failure

to

pick

up

vouchers

for

two

consecutive

months

resulted

in

administrative

termination

from

the

pro-

gram.

Administrative

termination

codes

were

noted

on

525

names.

Specific

causes

for

termination

were

known

for

172

of

the

names,

while

353

names

remained

unaccounted

for.

As

this

was

a

study of

women

who

actively

participated

in

WIC,

all

525

women

with

termination

codes

were

excluded

from

the

study,

leaving

4,373

eligible

participants.

Second,

each

mother's

name

(plus

town

of

residence,

race,

and

expected

date

of

delivery)

obtained

from

the

WIC

reports

was

linked,

by

hand,

to

the

corresponding

infant's

birth

certificate

record

listed

in

the

state's

computerized

Birth

Registry

file.

Twin

births

(46)

and

know

fetal

deaths

(15)

were

excluded,

as

were

191

names

which

could

not

be

positively

linked.

Third,

each

WIC

participant

was

individually

matched

to

a

control

subject

on

the

basis

of

five

maternal

characteris-

tics

available

on

the

birth

certificates:

age,

race,

parity,

educational

level,

and

marital

status

(Appendix

B).

Controls

were

selected

from

the

pool

of

64,000

remaining

non-WIC

births

in

the

computerized

State

Birth

Registry

(68,000

total

1978

resident

births

minus

the

approximately

4,000

WIC

births).

Matching

was

performed

by

hand

with

the

aid

of

computer-derived

lists.

Efforts

were

made

to

facilitate

geo-

graphic

similarity

of

the

WIC

and

control

populations;

matching

was

attempted

first

within

the

same

catchment

area,

then

within

similar

types

of

towns,

and

finally

any-

where

within

the

state.

The

first

eligible

woman

meeting

all

five

study

criteria

was

chosen.

All

matching

was

exact.**

Five

subjects

who

could

not

be

matched

were

excluded.

The

final

sample,

composed

of

4,126

matched

pairs

of

*

Detailed

procedure

manual

available

from

authors

upon

request.

**

Since

the

computerized

birth

registry

is

sequenced

by

date

of

birth,

the

control

subjects

tend

to

be

bom

earlier

in

the

year.

Given

the

expansion

of

the

WIC

program

in

Massachusetts

during

1978,

the

WIC

subjects

tend

to

be

born

later

in

the

year.

No

seasonality

bias

in

birth

outcomes

was

noticed.

WIC

and

non-WIC

mothers,

included

95

per

cent

of

all

eligible

1978

prenatal

WIC

participants

in

Massachusetts.

Derivation

of

Study

Data

Once

the

WIC

cases

and

matched

controls

were

select-

ed,

all

data

from

their

birth

certificates

were

extracted

for

analysis.

The

Massachusetts

birth

certificate

provides

data

on

maternal

demographic

characteristics,

prenatal

care,

and

pregnancy

outcomes.6

The

State

Death

Registry

file

pro-

vides

information

on

all

neonatal

deaths

between

birth

and

28

days.

Data

Analysis

The

demographic

characteristics

of

WIC

participants

were

contrasted

with

the

characteristics

of

all

pregnant

women

residing

in

the

same

catchment

area

and

statewide

in

1978.

WIC

participants

were

then

compared

directly

to

their

matched

non-WIC

controls

on

the

birth

outcome

measures.

Differences

were

statistically

examined

by

use

of

paired

T-

test

comparisons

for

continuous

data

items

and

by

McNemar

Chi-square

comparisons

for

ordinal

data

items.

Pairwise

deletions

were

used

for

any

subject

pair

having

missing

data.

The

women

in

the

WIC

sample

and

their

matched

controls

were

then

stratified

into

a

number

of

subpopulations

for

separate

analyses

of

birth

outcome

differences.

These

sub-

groups

were

defined

on

the

basis

of

demographic

character-

istics

or

duration

of

WIC

participation

and

are

not

statistical-

ly

independent

of

each

other.

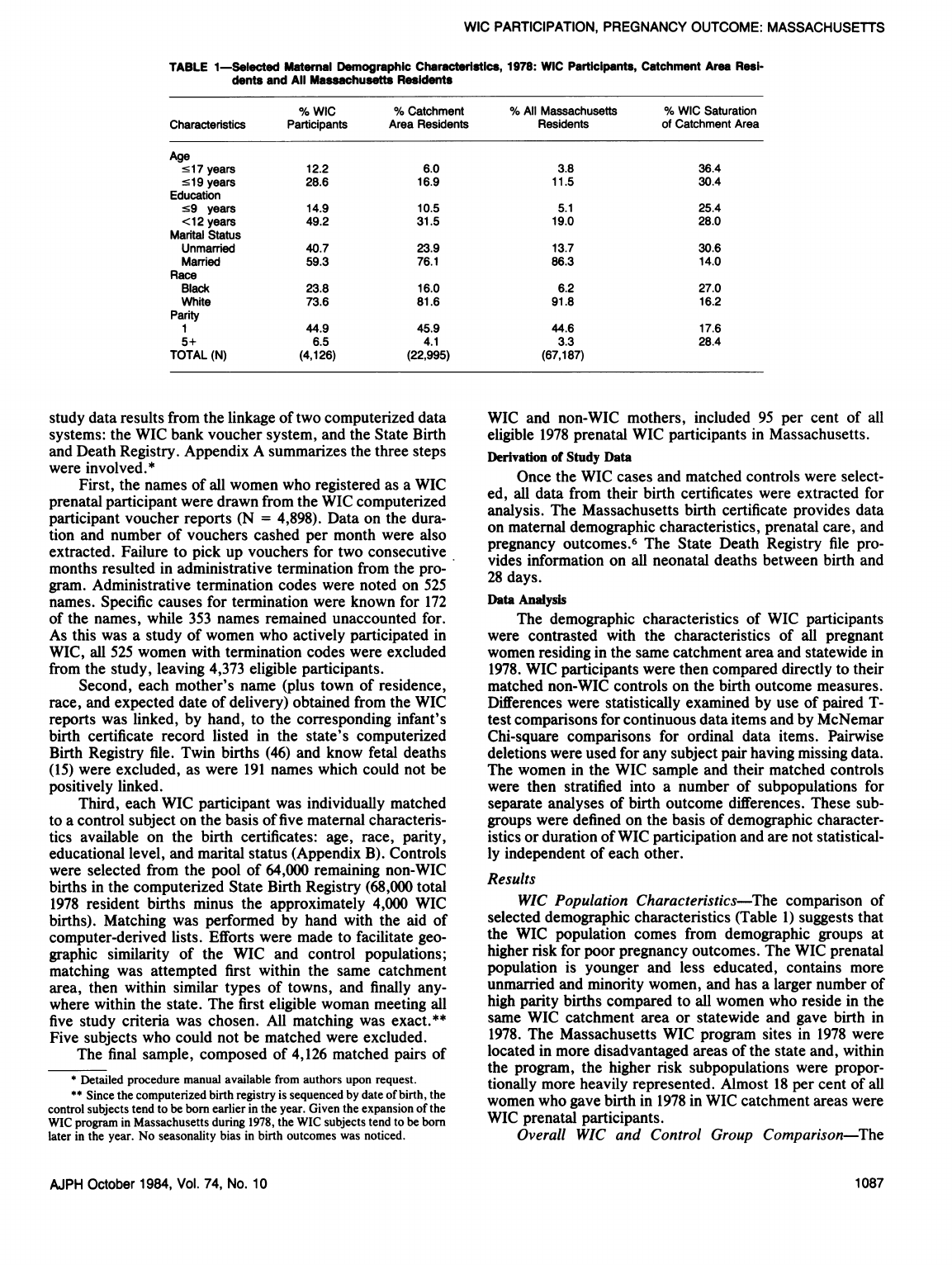

Results

WIC

Population

Characteristics-The

comparison

of

selected

demographic

characteristics

(Table

1)

suggests

that

the

WIC

population

comes

from

demographic

groups

at

higher

risk

for

poor

pregnancy

outcomes.

The

WIC

prenatal

population

is

younger

and

less

educated,

contains

more

unmarried

and

minority

women,

and

has

a

larger

number

of

high

parity

births

compared

to

all

women

who

reside

in

the

same

WIC

catchment

area

or

statewide

and

gave

birth

in

1978.

The

Massachusetts

WIC

program

sites

in

1978

were

located

in

more

disadvantaged

areas

of

the

state

and,

within

the

program,

the

higher

risk

subpopulations

were

propor-

tionally

more

heavily

represented.

Almost

18

per

cent

of

all

women

who

gave

birth

in

1978

in

WIC

catchment

areas

were

WIC

prenatal

participants.

Overall

WIC

and

Control

Group

Comparison-The

AJPH

October

1984,

Vol.

74,

No.

10

1087

KOTELCHUCK,

ET

AL.

TABLE

2-Comparlson

of

WIC

and

Control

Birth

Outcomes

95%

Confidence

Findings

N

WiC

Control

Difference

Interval

Birthweight

Birthweight

(in

grams)

4121

3281

3260

+210

t23.4

Per

Cent

Low

Birthweight

4121

6.9

8.7

-1.8**

±1.1

Per

Cent

Small

for

Gestational

Aget

3615

5.0

5.0

0.0

±1.0

Gestation

Adjusted

Birthweight

(in

grams)tt

4121

-52.0 -48.4

-3.6

±21.9

Gestation

Gestational

Age

(in

weeks)

3722

40.0

39.7

+0.3***

+.1

Per

Cent

Premature

(<37

weeks)

3722

8.5

9.8

-1.3'

±1.3

Morbidity

Per

Cent

with

Complications

of

Pregnancy,

Delivery

and

Labor

4115

20.2

21.1

-0.9

±1.7

Per

Cent

with

Congenital

Malformations

4126

1.7

1.7

0.0

±0.6

Per

Cent

Low

(<5)

Apgar

Score

(one

minute)

3732

5.1

5.7

-0.6

±1.0

Per

Cent

Low

(<5)

Apgar

Score

(five

minute)

3716

.5

1.0

-0.5*

±0.4

Mortality

Number

of

Neonatal

Deaths

4126

12

35

-23**

+13

Prenatal

Care

Number

of

Prenatal

Visits

3721

11.2

10.8

+0.4***

±0.2

Month

Prenatal

Care

Began

3721

2.7

2.9

-0.2***

±0.1

Adequacy

of

Prenatal

Care

indexttt

3675

1.34

1.41

-0.07***

±0.03

Per

Cent

with

Inadequate

Care

-

3.9

7.0

-3.1"'

±1.0

Per

Cent

with

Intermediate

Care

-

26.7

26.7

0.0

±2.0

Per

Cent

with

Adequate

Care

-

69.4

66.3

+3.1"

±2.1

0

p

<

.10.

=

p

<

.05.

=p

<.01.

=p

<

.001.

tSmall

for

gestational

ages

is

defined

as

an

infant

weighing

below

the

1

0th

percentile

for

their

gestational

age

at

birth.

Figures

derived

from

Battaglia

and

Lubchecno.7

ttThe

gestational

correction

for

birthweight

is

determined

by

subtracting

the

observed

birthweight

from

the

mean

Massachusetts

birthweight

for

that

gestational

age.

tttThe

Institute

of

Medicine

adequacy

of

prenatal

care

index

is

a

3-point

index

combining

the

number

of

prenatal

visits

and

month

prenatal

care

began,

with

an

adjustment

for

gestational

age.

Adequate

care

assumes

that

the

first

prenatal

care

visit

occurs

in

1st

trimester,

with

one

additional

visit

per

month

of

pregnancy.8

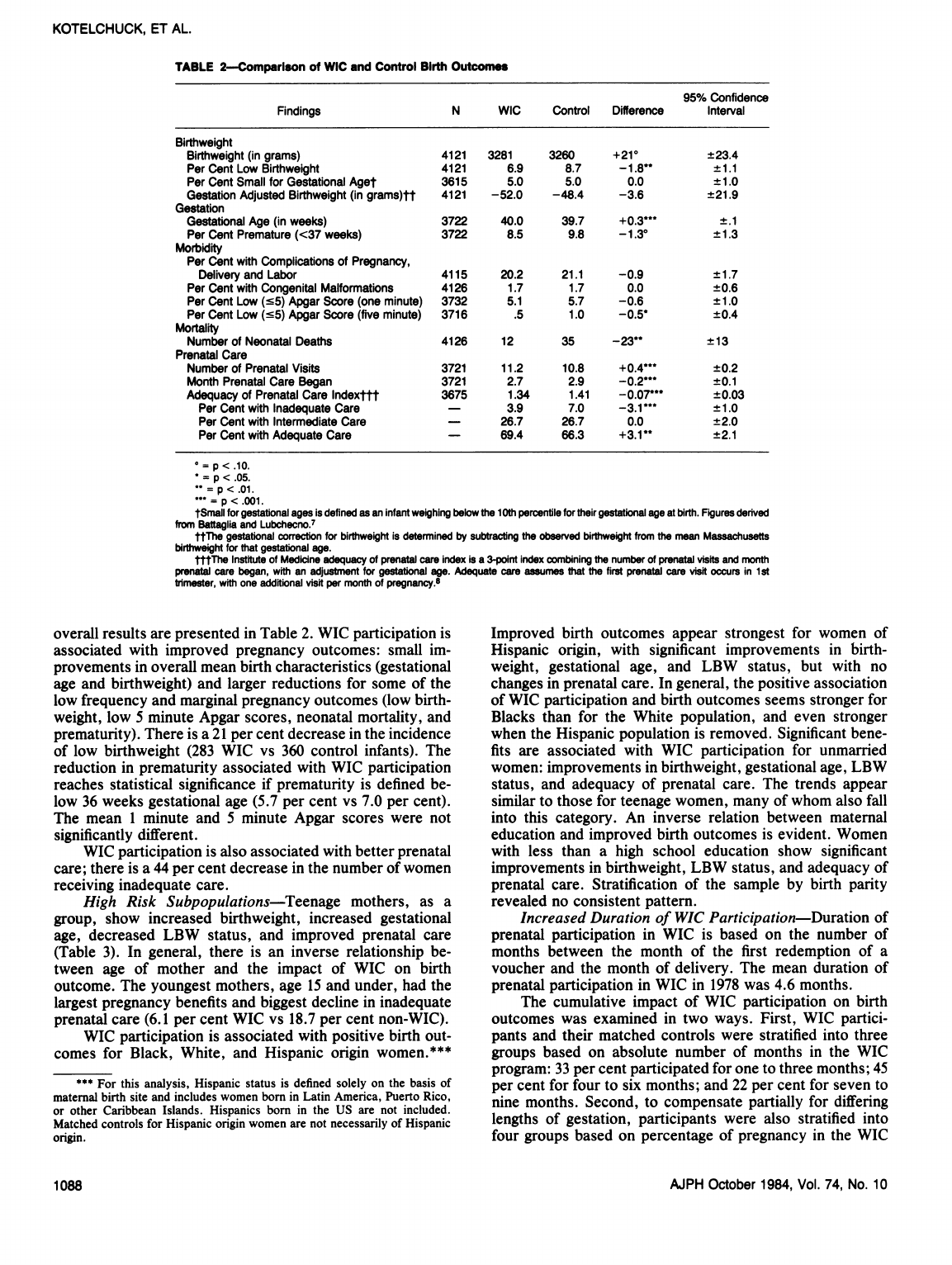

overall

results

are

presented

in

Table

2.

WIC

participation

is

associated

with

improved

pregnancy

outcomes:

small

im-

provements

in

overall

mean

birth

characteristics

(gestational

age

and

birthweight)

and

larger

reductions

for

some

of

the

low

frequency

and

marginal

pregnancy

outcomes

(low

birth-

weight,

low

5

minute

Apgar

scores,

neonatal

mortality,

and

prematurity).

There

is

a

21

per

cent

decrease

in

the

incidence

of

low

birthweight

(283

WIC

vs

360

control

infants).

The

reduction

in

prematurity

associated

with

WIC

participation

reaches

statistical

significance

if

prematurity

is

defined

be-

low

36

weeks

gestational

age

(5.7

per

cent

vs

7.0

per

cent).

The

mean

1

minute

and

5

minute

Apgar

scores

were

not

significantly

different.

WIC

participation

is

also

associated

with

better

prenatal

care;

there

is

a

44

per

cent

decrease

in

the

number

of

women

receiving

inadequate

care.

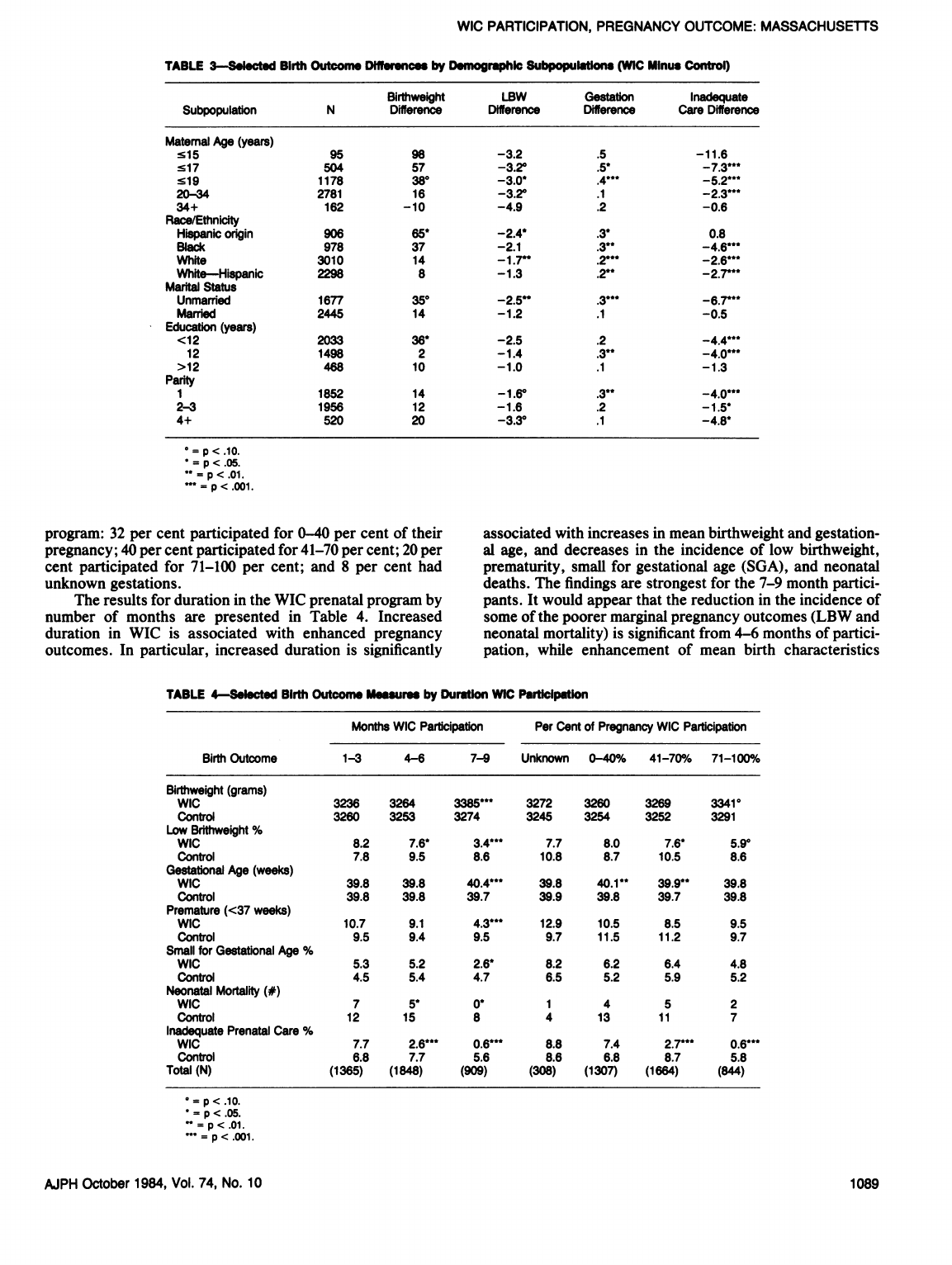

High

Risk

Subpopulations-Teenage

mothers,

as

a

group,

show

increased

birthweight,

increased

gestational

age,

decreased

LBW

status,

and

improved

prenatal

care

(Table

3).

In

general,

there

is

an

inverse

relationship

be-

tween

age

of

mother

and

the

impact

of

WIC

on

birth

outcome.

The

youngest

mothers,

age

15

and

under,

had

the

largest

pregnancy

benefits

and

biggest

decline

in

inadequate

prenatal

care

(6.1

per

cent

WIC

vs

18.7

per

cent

non-WIC).

WIC

participation

is

associated

with

positive

birth

out-

comes

for

Black,

White,

and

Hispanic

origin

women.***

***

For

this

analysis,

Hispanic

status

is

defined

solely

on

the

basis

of

maternal

birth

site

and

includes

women

born

in

Latin

America,

Puerto

Rico,

or

other

Caribbean

Islands.

Hispanics

born

in

the

US

are

not

included.

Matched

controls

for

Hispanic

origin

women

are

not

necessarily

of

Hispanic

origin.

Improved

birth

outcomes

appear

strongest

for

women

of

Hispanic

origin,

with

significant

improvements

in

birth-

weight,

gestational

age,

and

LBW

status,

but

with

no

changes

in

prenatal

care.

In

general,

the

positive

association

of

WIC

participation

and

birth

outcomes

seems

stronger

for

Blacks

than

for

the

White

population,

and

even

stronger

when

the

Hispanic

population

is

removed.

Significant

bene-

fits

are

associated

with

WIC

participation

for

unmarried

women:

improvements

in

birthweight,

gestational

age,

LBW

status,

and

adequacy

of

prenatal

care.

The

trends

appear

similar

to

those

for

teenage

women,

many

of

whom

also

fall

into

this

category.

An

inverse

relation

between

maternal

education

and

improved

birth

outcomes

is

evident.

Women

with

less

than

a

high

school

education

show

significant

improvements

in

birthweight,

LBW

status,

and

adequacy

of

prenatal

care.

Stratification

of

the

sample

by

birth

parity

revealed

no

consistent

pattern.

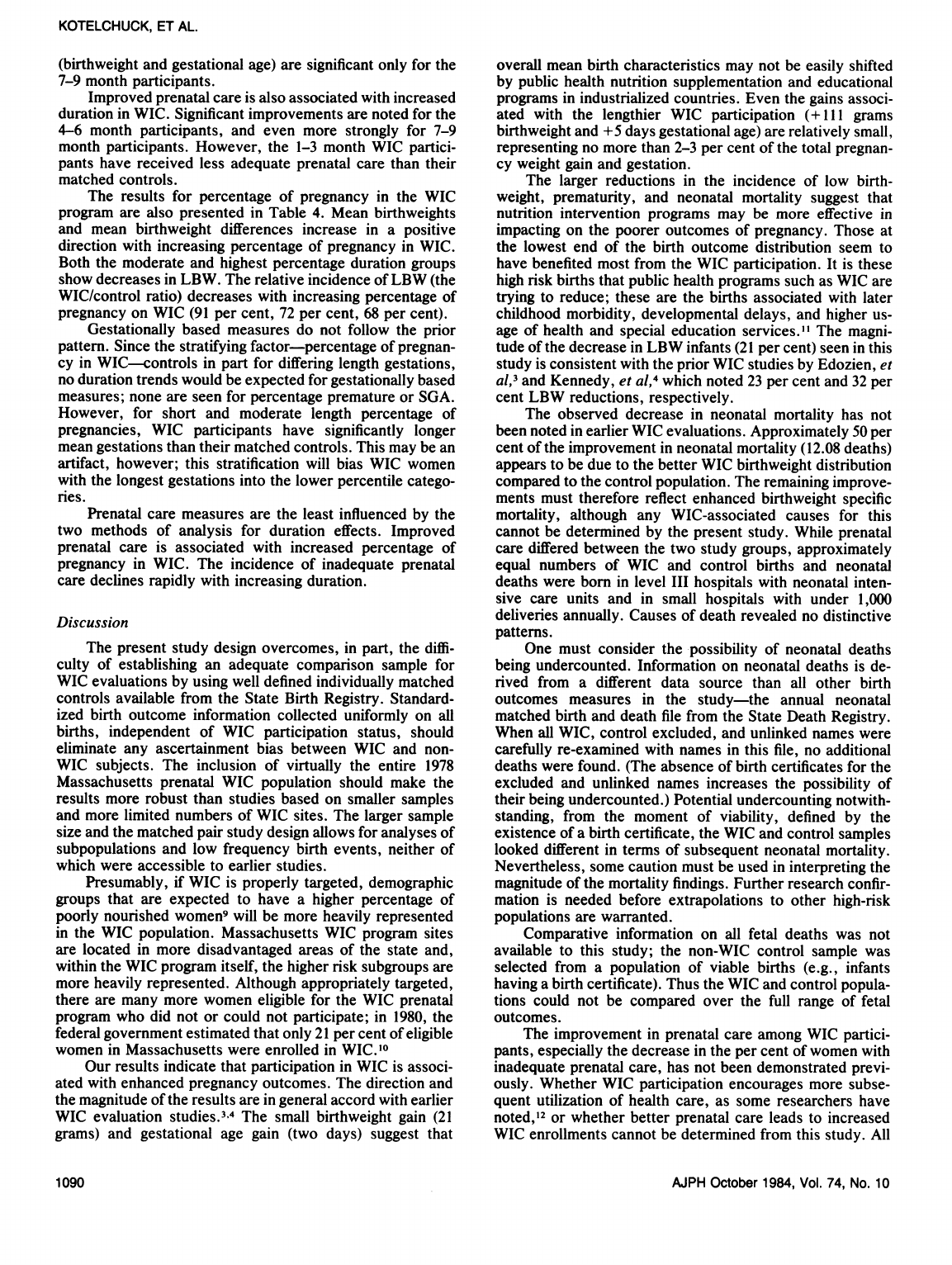

Increased

Duration

of

WIC

Participation-Duration

of

prenatal

participation

in

WIC

is

based

on

the

number

of

months

between

the

month

of

the

first

redemption

of

a

voucher

and

the

month

of

delivery.

The

mean

duration

of

prenatal

participation

in

WIC

in

1978

was

4.6

months.

The

cumulative

impact

of

WIC

participation

on

birth

outcomes

was

examined

in

two

ways.

First,

WIC

partici-

pants

and

their

matched

controls

were

stratified

into

three

groups

based

on

absolute

number

of

months

in

the

WIC

program:

33

per

cent

participated

for

one

to

three

months;

45

per

cent

for

four

to

six

months;

and

22

per

cent

for

seven

to

nine

months.

Second,

to

compensate

partially

for

differing

lengths

of

gestation,

participants

were

also

stratified

into

four

groups

based

on

percentage

of

pregnancy

in

the

WIC

AJPH

October

1984,

Vol.

74,

No.

10

1088

WIC

PARTICIPATION,

PREGNANCY

OUTCOME:

MASSACHUSETTS

TABLE

3-Selcted

Birth

Outcome

Dier

by

Dmographic

Subpopuations

(WIC

Minus

Control)

Birthweight

LBW

Gestation

Inadequate

Subpopulation

N

Difference

Difference

Difference

Care

Difference

Matemal

Age

(years)

s15

95

98

-3.2

.5

-11.6

s17

504 57

-3.20

.5*

-7.3***

519

1178

380

-3.0*

.4***

-5.2***

20-34

2781

16

-3.2°

.1

-2.3***

34+

162

-10

-4.9

.2

-0.6

Race/Ethnicity

Hispanic

origin

906

65*

-2.4*

.3'

0.8

Black

978

37

-2.1

.3

-4.6***

White

3010

14

-1.7"

.2***

-2.6***

White-Hispanic

2298

8

-1.3

.2**

-2.7'

Marital

Status

Unmarried

1677

350

-2.5*"

.3***

-6.r**

Married

2445

14

-1.2

.1

-0.5

Education

(years)

<12

2033

36*

-2.5

.2

-4.4***

12

1498

2

-1.4

.3*"

-4.0**"

>12

468

10

-1.0

.1

-1.3

Parity

1

1852

14

-1.6'

.3**

-4.0"**

2-3

1956

12

-1.6

.2

-1.5*

4+

520

20

-3.3'

.1

-4.8*

o

p

<

.10.

p

<

.05.

=p

<.01.

'=p

<.0o1.

program:

32

per

cent

participated

for

0-40

per

cent

of

their

pregnancy;

40

per

cent

participated

for

41-70

per

cent;

20

per

cent

participated

for

71-100

per

cent;

and

8

per

cent

had

unknown

gestations.

The

results

for

duration

in

the

WIC

prenatal

program

by

number

of

months

are

presented

in

Table

4.

Increased

duration

in

WIC

is

associated

with

enhanced

pregnancy

outcomes.

In

particular,

increased

duration

is

significantly

associated

with

increases

in

mean

birthweight

and

gestation-

al

age,

and

decreases

in

the

incidence

of

low

birthweight,

prematurity,

small

for

gestational

age

(SGA),

and

neonatal

deaths.

The

findings

are

strongest

for

the

7-9

month

partici-

pants.

It

would

appear

that

the

reduction

in

the

incidence

of

some

of

the

poorer

marginal

pregnancy

outcomes

(LBW

and

neonatal

mortality)

is

significant

from

4-6

months

of

partici-

pation,

while

enhancement

of

mean

birth

characteristics

TABLE

4-Selcted

Birth

Outcome

Meurse

by

Duration

WIC

Participation

Months

WIC

Participation

Per

Cent

of

Pregnancy

WIC

Participation

Birth

Outcome

1-3

4-6

7-9

Unknown

0-40%

41-70%

71-100%O

Birthweight

(grams)

WiC

3236

3264

3385"'

3272

3260

3269

3341'

Control

3260 3253

3274

3245

3254

3252

3291

Low

Brithweight

%

WIC

8.2

7.6'

3.4"*'

7.7

8.0

7.6*

5.9'

Control

7.8 9.5 8.6

10.8

8.7

10.5

8.6

Gestational

Age

(weeks)

WiC

39.8

39.8

40.4*"*

39.8

40.1"

39.9"*

39.8

Control

39.8

39.8

39.7

39.9

39.8

39.7

39.8

Premature

(<37

weeks)

WiC

10.7

9.1

4.3"*'

12.9

10.5

8.5

9.5

Control

9.5

9.4

9.5

9.7

11.5

11.2

9.7

Small

for

Gestational

Age

%

WiC

5.3

5.2

2.6*

8.2

6.2

6.4

4.8

Control

4.5

5.4

4.7

6.5

5.2

5.9

5.2

Neonatal

Mortality

(#)

WIC

7

5*

0*

1

4

5

2

Control

12

15

8

4

13

11

7

Inadequate

Prenatal

Care

%

WIC

7.7

2.6"**

0.6*"'

8.8

7.4

2.7"**

0.6***

Control

6.8

7.7

5.6

8.6

6.8

8.7

5.8

Total

(N)

(1365) (1848)

(909)

(308)

(1307)

(1664)

(844)

p

<

.10.

p

<

.05.

=

p

<

.01.

=p

<

.001.

AJPH

October

1984,

Vol.

74,

No.

10

1089

KOTELCHUCK,

ET

AL.

(birthweight

and

gestational

age)

are

significant

only

for

the

7-9

month

participants.

Improved

prenatal

care

is

also

associated

with

increased

duration

in

WIC.

Significant

improvements

are

noted

for

the

4-6

month

participants,

and

even

more

strongly

for

7-9

month

participants.

However,

the

1-3

month

WIC

partici-

pants

have

received

less

adequate

prenatal

care

than

their

matched

controls.

The

results

for

percentage

of

pregnancy

in

the

WIC

program

are

also

presented

in

Table

4.

Mean

birthweights

and

mean

birthweight

differences

increase

in

a

positive

direction

with

increasing

percentage

of

pregnancy

in

WIC.

Both

the

moderate

and

highest

percentage

duration

groups

show

decreases

in

LBW.

The

relative

incidence

of

LBW

(the

WIC/control

ratio)

decreases

with

increasing

percentage

of

pregnancy

on

WIC

(91

per

cent,

72

per

cent,

68

per

cent).

Gestationally

based

measures

do

not

follow

the

prior

pattern.

Since

the

stratifying

factor-percentage

of

pregnan-

cy

in

WIC-controls

in

part

for

differing

length

gestations,

no

duration

trends

would

be

expected

for

gestationally

based

measures;

none

are

seen

for

percentage

premature

or

SGA.

However,

for

short

and

moderate

length

percentage

of

pregnancies,

WIC

participants

have

significantly

longer

mean

gestations

than

their

matched

controls.

This

may

be

an

artifact,

however;

this

stratification

will

bias

WIC

women

with

the

longest

gestations

into

the

lower

percentile

catego-

ries.

Prenatal

care

measures

are

the

least

influenced

by

the

two

methods

of

analysis

for

duration

effects.

Improved

prenatal

care

is

associated

with

increased

percentage

of

pregnancy

in

WIC.

The

incidence

of

inadequate

prenatal

care

declines

rapidly

with

increasing

duration.

Discussion

The

present

study

design

overcomes,

in

part,

the

diffi-

culty

of

establishing

an

adequate

comparison

sample

for

WIC

evaluations

by

using

well

defined

individually

matched

controls

available

from

the

State

Birth

Registry.

Standard-

ized

birth

outcome

information

collected

uniformly

on

all

births,

independent

of

WIC

participation

status,

should

eliminate

any

ascertainment

bias

between

WIC

and

non-

WIC

subjects.

The

inclusion

of

virtually

the

entire

1978

Massachusetts

prenatal

WIC

population

should

make

the

results

more

robust

than

studies

based

on

smaller

samples

and

more

limited

numbers

of

WIC

sites.

The

larger

sample

size

and

the

matched

pair

study

design

allows

for

analyses

of

subpopulations

and

low

frequency

birth

events,

neither

of

which

were

accessible

to

earlier

studies.

Presumably,

if

WIC

is

properly

targeted,

demographic

groups

that

are

expected

to

have

a

higher

percentage

of

poorly

nourished

women9

will

be

more

heavily

represented

in

the

WIC

population.

Massachusetts

WIC

program

sites

are

located

in

more

disadvantaged

areas

of

the

state

and,

within

the

WIC

program

itself,

the

higher

risk

subgroups

are

more

heavily

represented.

Although

appropriately

targeted,

there

are

many

more

women

eligible

for

the

WIC

prenatal

program

who

did

not

or

could

not

participate;

in

1980,

the

federal

government

estimated

that

only

21

per

cent

of

eligible

women

in

Massachusetts

were

enrolled

in

WIC.10

Our

results

indicate

that

participation

in

WIC

is

associ-

ated

with

enhanced

pregnancy

outcomes.

The

direction

and

the

magnitude

of

the

results

are

in

general

accord

with

earlier

WIC

evaluation

studies.34

The

small

birthweight

gain

(21

grams)

and

gestational

age

gain

(two

days)

suggest

that

overall

mean

birth

characteristics

may

not

be

easily

shifted

by

public

health

nutrition

supplementation

and

educational

programs

in

industrialized

countries.

Even

the

gains

associ-

ated

with

the

lengthier

WIC

participation

(+

111

grams

birthweight

and

+5

days

gestational

age)

are

relatively

small,

representing

no

more

than

2-3

per

cent

of

the

total

pregnan-

cy

weight

gain

and

gestation.

The

larger

reductions

in

the

incidence

of

low

birth-

weight,

prematurity,

and

neonatal

mortality

suggest

that

nutrition

intervention

programs

may

be

more

effective

in

impacting

on

the

poorer

outcomes

of

pregnancy.

Those

at

the

lowest

end

of

the

birth

outcome

distribution

seem

to

have

benefited

most

from

the

WIC

participation.

It

is

these

high

risk

births

that

public

health

programs

such

as

WIC

are

trying

to

reduce;

these

are

the

births

associated

with

later

childhood

morbidity,

developmental

delays,

and

higher

us-

age

of

health

and

special

education

services."

The

magni-

tude

of

the

decrease

in

LBW

infants

(21

per

cent)

seen

in

this

study

is

consistent

with

the

prior

WIC

studies

by

Edozien,

et

al,3

and

Kennedy,

et

al,4

which

noted

23

per

cent

and

32

per

cent

LBW

reductions,

respectively.

The

observed

decrease

in

neonatal

mortality

has

not

been

noted

in

earlier

WIC

evaluations.

Approximately

50

per

cent

of

the

improvement

in

neonatal

mortality

(12.08

deaths)

appears

to

be

due

to

the

better

WIC

birthweight

distribution

compared

to

the

control

population.

The

remaining

improve-

ments

must

therefore

reflect

enhanced

birthweight

specific

mortality,

although

any

WIC-associated

causes

for

this

cannot

be

determined

by

the

present

study.

While

prenatal

care

differed

between

the

two

study

groups,

approximately

equal

numbers

of

WIC

and

control

births

and

neonatal

deaths

were

born

in

level

III

hospitals

with

neonatal

inten-

sive

care

units

and

in

small

hospitals

with

under

1,000

deliveries

annually.

Causes

of

death

revealed

no

distinctive

patterns.

One

must

consider

the

possibility

of

neonatal

deaths

being

undercounted.

Information

on

neonatal

deaths

is

de-

rived

from

a

different

data

source

than

all

other

birth

outcomes

measures

in

the

study-the

annual

neonatal

matched

birth

and

death

file

from

the

State

Death

Registry.

When

all

WIC,

control

excluded,

and

unlinked

names

were

carefully

re-examined

with

names

in

this

file,

no

additional

deaths

were

found.

(The

absence

of

birth

certificates

for

the

excluded

and

unlinked

names

increases

the

possibility

of

their

being

undercounted.)

Potential

undercounting

notwith-

standing,

from

the

moment

of

viability,

defined

by

the

existence

of

a

birth

certificate,

the

WIC

and

control

samples

looked

different

in

terms

of

subsequent

neonatal

mortality.

Nevertheless,

some

caution

must

be

used

in

interpreting

the

magnitude

of

the

mortality

findings.

Further

research

confir-

mation

is

needed

before

extrapolations

to

other

high-risk

populations

are

warranted.

Comparative

information

on

all

fetal

deaths

was

not

available

to

this

study;

the

non-WIC

control

sample

was

selected

from

a

population

of

viable

births

(e.g.,

infants

having

a

birth

certificate).

Thus

the

WIC

and

control

popula-

tions

could

not

be

compared

over

the

full

range

of

fetal

outcomes.

The

improvement

in

prenatal

care

among

WIC

partici-

pants,

especially

the

decrease

in

the

per

cent

of

women

with

inadequate

prenatal

care,

has

not

been

demonstrated

previ-

ously.

Whether

WIC

participation

encourages

more

subse-

quent

utilization

of

health

care,

as

some

researchers

have

noted,'2

or

whether

better

prenatal

care

leads

to

increased

WIC

enrollments

cannot

be

determined

from

this

study.

All

AJPH

October

1984,

Vol.

74,

No.

10

1090

WIC

PARTICIPATION,

PREGNANCY

OUTCOME:

MASSACHUSETTS

prenatal

WIC

participants

must

document

their

pregnancy

status,

an

act

that

encourages

a

formal

prenatal

care

visit

and

thereby

increases

the

likelihood

of

being

drawn

at

an

early

stage

into

a

prenatal

care

health

network.

Improved

prenatal

care

is

both

an

important

goal

and

an

achievement

of

the

WIC

program.

Benefits

associated

with

WIC

participation

do

not

ap-

pear

limited

to

any

particular

population

group,

but

are

seen

across

a

wide

spectrum

of

subpopulations.

Subpopulations

at

higher

nutritional

risk

for

poor

pregnancy

outcomes,

however,

appear

to

benefit

more

strongly,

especially

teen-

age,

unmarried,

and

Hispanic

origin

women.

In

general,

the

neediest

populations

seem

to

benefit

the

most

from

the

WIC

program.

Increased

duration

of

participation

in

the

WIC

program

appears

to

be

associated

with

enhanced

birth

outcomes,

in

general

accord

with

prior

WIC

research.3'4

The

birth

out-

comes

for

the

longest

duration

WIC

participants

reach

or

surpass

the

State's

overall

mean

birthweight

(3343

grams)

and

incidence

of

LBW

(6.55

per

cent).

Estimating

the

exact

magnitude

of

the

cumulative

bene-

fits

associated

with

increased

duration

of

participation

in

WIC

is

methodologically

complicated.

Duration

of

participa-

tion

and

gestational

age

are,

in

part,

confounded.

WIC

benefits

may

be

mediated

through

increased

gestational

age

but

in

turn,

increased

gestational

age

allows

for

increased

duration

in

WIC.

Any

grouping

of

subjects

for

statistical

analysis

on

the

basis

of

extensive

absolute

duration

of

participation

in

WIC

virtually

assures

that

they

have

longer

gestations

and

higher

birthweight;

while

any

statistical

cor-

rections

for

length

of

gestation

will

eliminate

the

benefits

associated

with

the

program's

enhancement

of

gestational

age.

Since

no

ideal

analytic

solution

exists,'3

we

used

two

alternative

methods:

absolute

duration

in

WIC,

and

percent-

age

of

pregnancy

in

WIC.

Since

the

absolute

duration

measure

may

be

an

over-estimation

and

the

percentage

of

pregnancy

may

be

an

under-estimation,

we

suggest

that

the

magnitude

of

the

cumulative

benefits

associated

with

WIC

should

fall

between

these

two

estimates.

Both

methods

of

analyses

imply

that

more

extensive

WIC

participation

is

associated

with

more

beneficial

birth

outcomes.

The

abso-

lute

duration

analysis

would

indicate

that

the

benefits

are

not

simply

linear;

WIC

participation

greater

than

six

months

would

appear

maximally

beneficial.

It

is

not

only

chance

or

self-motivation

that

determines

if

a

person

enters

WIC

early

or

late.

Barriers

and

incentives

to

early

participation

exist.

Haddad

and

Willis'4

have

shown

that

the

probability

of

women

entering

WIC

in

their

first

three

months

of

pregnancy

is

significantly

enhanced

if

the

WIC

program

site

has

been

open

a

long

time,

delivers

it

supplementation

through

retail

stores,

and

uses

public

ser-

vice

announcements.

The

potential

benefits

associated

with

the

WIC

program

are

not

yet

being

reached;

only

22

per

cent

of

the

WIC

prenatal

participants

participated

for

more

than

six

months.

The

comprehensiveness

of

the

case

population

is

an

important

element

in

assessing

the

validity

and

generalizabi-

lity

of

the

present

study.

The

names

of

525

women

adminis-

tratively

excluded

from

the

WIC

prenatal

program

were

omitted

from

this

study.

Unfortunately,

very

little

demo-

graphic

or

motivational

information

is

available

about

them

from

the

WIC

computerized

records.

The

353

names,

which

had

no

reason

specified

for

their

exclusion,

were

similar

racially

to

the

WIC

study

population

(68.6

per

cent

White

excluded

group

vs

73.6

per

cent

study

group).

We

are

doubtful

that

most

of

these

353

names

led

to

an

actual

Massachusetts

birth.

Less

than

10

per

cent

of

these

women

had

locatable

birth

certificates.

Abortions,

fraud,

computer

errors,

and

out-of-state

moves

are

the

more

likely

unrecord-

ed

realities

for

these

names.t

Women

do

not

always

inform

the

WIC

program

of

their

reasons

for

discontinuance.

Nev-

ertheless,

one

cannot

rule

out

of

the

possibility

that

the

administratively

excluded

names

may

have

had

specific

characteristics

which

would

bias

the

overall

study

results.

The

birth

certificates

for

191

women

who

were

in

the

WIC

program

prenatally

could

not

be

located.

Again,

little

epidemiologic

information

is

available

about

these

women.

Racially

(based

on

their

WIC

records)

they

are

similar;

their

duration

of

participation

in

WIC

is

essentially

the

same

as

the

WIC

group.

No

fetal

deaths

were

located

among

this

group.

One

can

not

rule

out

the

possibility

that

they

may

have

had

specific

characteristics

which

would

bias

the

overall

results.

Five

WIC

women

with

birth

certificates

were

not

matched

to

controls.

Overall,

we

estimate

that

at

least

95

per

cent

of

the

WIC

prenatal

participant

population

were

included

in

the

study

which

represents

the

largest

and

most

comprehensive

series

on

WIC

prenatal

participants

to

date.

Establishing

the

existence

and

magnitude

of

a

WIC

program

effect

also

depends

critically

on

the

comparability

of

the

WIC

and

matched

control

groups.

Unfortunately,

there

are

inherent

limitations

to

the

conclusions

that

can

be

drawn

from

a

retrospective

cohort

study

in

which

the

exposure

(WIC)

group

is

self-selected

and

the

control

group

is

derived

by

a

post-hoc

matching

procedure.

A

more

ideal

randomized

case

control

study

would

pose

serious

ethical

dilemmas.

Since

many

known

confounding

factors

have

been

controlled,

we

believe

that

the

statistical

differences

between

the

WIC

and

control

groups

are

a

function

of

WIC

participation;

however,

additional

confounding

factors

may

also

be

characteristic

of

the

WIC

or

control

populations

and

account

for

any

birth

outcome

differences

noted.

The

Massachusetts

birth

certificates

do

not

provide

specific

information

on

maternal

pre-pregnancy

weight

or

height,

maternal

weight

gain,

maternal

smoking

habits,

or

maternal

morbidity.

Any

of

these

factors,

if

unevenly

distrib-

uted,

may

be

sufficient

to

distort

the

overall

outcomes.

WIC

participants

may

be

more

strongly

motivated

to

improve

the

prenatal

health

of

their

future

offspring

than

are

the

control

women.

Such

a

motivational

difference

could

cause

both

an

improvement

in

pregnancy

outcome

and

a

desire

to

enroll

in

the

WIC

program.

The

findings

of

earlier

and

more

frequent

prenatal

care

visits

may

be

supportive

of

this

view.

The

increase

in

prenatal

care

may

also

be

the

cause

of

the

improved

birth

outcomes,

and

not

simply

another

conse-

quence

of

WIC

participation.

The

lack

of

prenatal

care

improvements

among

Hispanic

origin

women

who

show

enhanced

birth

outcomes

argues

somewhat

against

this

interpretation.

The

present

study

design

does

not

lend

itself

to

a

study

of

prenatal

care,

nutrition

supplementation,

or

nutrition

counseling

independently

of

each

other.

Although

these

alternative

explanations

for

the

birth

outcome

differences

tend

to

suggest

that

the

attributed

WIC

program

effects

may

be

over-estimated,

an

under-estimation

may

be

just

as

likely.

The

WIC

population

could

be

financial-

t

Women

who

delivered

prematurely,

even

shortly

after

joining

the

WIC

program,

would

not

be

administratively

excluded;

these

women

would

be

switched

to

the

WIC

postpartum

program

and

their birth

records

included

in

this

study.

AJPH

October

1984,

Vol.

74,

No.

10

1091

KOTELCHUCK,

ET

AL.

ly

poorer

and

at

greater

obstetric

risk

than

their

matched

controls.

All

WIC

participants

must

have

an

income

under

195

per

cent

of

the

poverty

level,

while

the

controls

have

no

restrictions

on

income,

and

presumably

some

have

higher

incomes.

Post-hoc

analyses

reveal

that

there

were

more

women

of

Hispanic

origin

in

the

WIC

than

the

control

sample

(906

vs

509).

And

WIC

participants

are

selected,

in

part,

on

the

basis

of

poor

prior

obstetrical

histories,

while

no

such

criteria

exists

for

the

control

group.

These

potential

confounding

factors

in

a

matched

study

design

would

de-

crease

the

likelihood

of

showing

positive

birth

outcomes

associated

with

WIC

participation.

In

summary,

the

Massachusetts

WIC

Statewide

Evalua-

tion

Project

compared

the

birth

outcomes

of

4,126

WIC

prenatal

participants

and

4,126

individually

matched

con-

trols,

utilizing

public

birth

and

death

certificates.

Results

showed

that

the

WIC

program

appears

to

be

targeted

to

women

at

high

demographic

risk

for

poor

pregnancy

out-

comes;

that

overall

WIC

participation

is

associated

with

small

improvements

in

mean

birth

characteristics,

larger

reductions

in

marginal

pregnancy

outcomes,

and

enhanced

prenatal

care;

and,

that

these

benefits

are

observed

more

strongly

in

higher

risk

subpopulations

and

are

enhanced

with

increased

duration

of

participation.

Based

on

the

informa-

tion

available

to

this

study,

we

conclude

that

participation

in

the

WIC

prenatal

program

is

associated

with

improved

pregnancy

outcomes

for

women

at

high

nutritional

and

financial

risk.

REFERENCES

1.

Public

Law

94-105,

USC

1786,

Section

14,

1975.

2.

Berkenfield

J,

Schwartz

JB:

Nutrition

intervention

in

the

community-

the

"WIC"

program.

N

Engi

J

Med

1980;

302:579-581.

3.

Edozien

JC,

Switzer

BR,

Bryan

RB.

Medical

evaluation

of

the

Special

Supplemental

Food

Program

for

Women,

Infants

and

Children.

Am

J

Clin

Nutr

1979;

32:677-682.

4.

Kennedy

ET,

Gershoff

S,

Reed

RB,

Austin

JE.

Evaluation

of

the

effect

of

WIC

supplemental

feeding

on

birth

weight.

J

Am

Dietet

Assoc

1982;

80:220-227.

5.

Rush

D:

Is

WIC

worthwhile?

(editorial)

Am

J

Public

Health

1982;

72:1101-1103.

6.

US

Dept

of

Health

and

Human

Services:

The

1978

Revision

of

the

US

Standard

Certificates.

DHHS

Pub.

No.

PHS

83-1460,

Series

4,

No.

23.

Washington,

DC:

Govt

Printing

Office,

1983.

7.

Battaglia

FC,

Lubchenco

LO:

A

practical

classification

of

newborn

infants

by

weight

and

gestational

age.

J

Pediatr

1967;

71:159-163.

8.

Kessner

DM,

Singer

J,

Kalk

CE,

Schlesinger

ER:

Infant

Death:

An

Analysis

of

Maternal

Risk

and

Health

Care.

Washington

DC:

Institute

of

Medicine,

National

Academy

of

Sciences,

1973.

9.

US

Dept

of

Health,

Education,

and

Welfare:

Caloric

and

Selected

Nutrient

Values

for

Persons

1-74

years

of

Age,

First

Health

and

Nutrition

Examination

Survey,

United

States,

1971-74.

DHEW

Pub.

No.

PHS

73-

1311,

Series

11,

No.

209.

Washington

DC:

Govt

Printing

Office,

1976.

10.

US

Dept

of

Health

and

Human

Services:

Better

Health

for

our

Children:

A

National

Strategy.

DHHS

Pub.

No.

PHS

79-55071,

Vol

III.

Washing-

ton,

DC:

Govt

Printing

Office,

1981.

11.

Fitzhardinge

PM:

Follow-up

studies

of

the

low

birthweight

infants.

Clin

Perinatol

1976;

3:503-516.

12.

Kotch

JB,

Whiteman

D:

Effect

of

a

WIC

program

on

children's

clinic

activity

in

a

local

health

department.

Med

Care

1982;

20:691-698.

13.

Harris

JE:

Prenatal

medical

care

and

infant

mortality.

In

Fuchs

VR

(ed):

Economic

Aspects

of

Health.

Chicago:

University

of

Chicago

Press,

1982.

14.

Haddad

LJ,

Willis

CE:

An

analysis

of

factors

leading

to

early

enrollment

in

the

Massachusetts

Special

Supplemental

Feeding

Program

for

Women,

Infants

and

Children.

Amherst:

Massachusetts

Experimental

Station

Research

Bulletin,

University

of

Massachusetts,

1983;

No.

682.

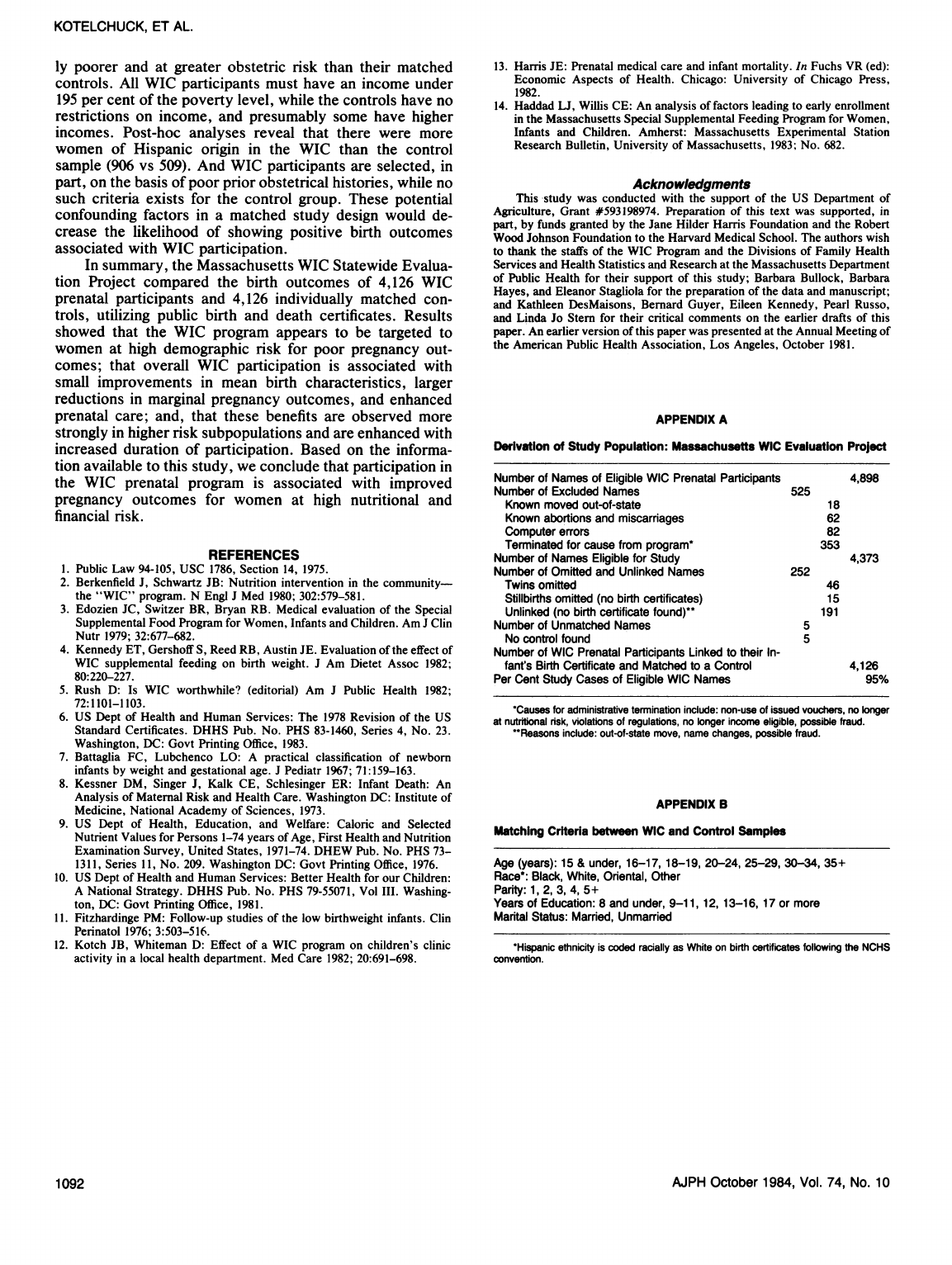

Acknowledgments

This study

was

conducted

with

the

support

of

the

US

Department

of

Agriculture,

Grant

#593198974.

Preparation

of

this

text

was

supported,

in

part,

by

funds

granted

by

the

Jane

Hilder

Harris

Foundation

and

the

Robert

Wood

Johnson

Foundation

to

the

Harvard

Medical

School.

The

authors

wish

to

thank

the

staffs

of

the

WIC

Program

and

the

Divisions

of

Family

Health

Services

and

Health

Statistics

and

Research

at

the

Massachusetts

Department

of

Public

Health

for

their

support

of

this

study;

Barbara

Bullock,

Barbara

Hayes,

and

Eleanor

Stagliola

for

the

preparation

of

the

data

and

manuscript;

and

Kathleen

DesMaisons,

Bernard

Guyer,

Eileen

Kennedy,

Pearl

Russo,

and

Linda

Jo

Stern

for

their

critical

comments

on

the

earlier

drafts

of

this

paper.

An

earlier

version

of

this

paper

was

presented

at

the

Annual