Understanding Discourse Communities

Dan Melzer

This essay is a chapter in Writing Spaces: Readings on Writing, Volume 3, a

peer-reviewed open textbook series for the writing classroom.

Download the full volume and individual chapters from any of these sites:

• Writing Spaces: http://writingspaces.org/essays

• Parlor Press: http://parlorpress.com/pages/writing-spaces

• WAC Clearinghouse: http://wac.colostate.edu/books/

Print versions of the volume are available for purchase directly from Parlor

Press and through other booksellers.

Parlor Press LLC, Anderson, South Carolina, USA

© 2020 by Parlor Press. Individual essays © 2020 by the respective authors. Unless

otherwise stated, these works are licensed under the Creative Commons Attribu-

tion-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND

4.0) and are subject to the Writing Spaces Terms of Use. To view a copy of this

license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/, email info@cre-

ativecommons.org, or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain

View, CA 94042, USA. To view the Writing Spaces Terms of Use, visit http://writ-

ingspaces.org/terms-of-use.

All rights reserved. For permission to reprint, please contact the author(s) of the

individual articles, who are the respective copyright owners.

Cover design by Colin Charlton.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data on File

100

7

Understanding Discourse

Communities

Dan Melzer

Overview

This chapter uses John Swales’ definition of discourse community to explain

to students why this concept is important for college writing and beyond.

The chapter explains how genres operate within discourse communities,

why different discourse communities have different expectations for writ-

ing, and how to understand what qualifies as a discourse community. The

article relates the concept of discourse community to a personal example

from the author (an acoustic guitar jam group) and an example of the

academic discipline of history. The article takes a critical stance regard-

ing the concept of discourse community, discussing both the benefits and

constraints of communicating within discourse communities. The article

concludes with writerly questions students can ask themselves as they enter

new discourse communities in order to be more effective communicators.

L

ast year, I decided that if I was ever going to achieve my lifelong

fantasy of being the first college writing teacher to transform into an

international rock star, I should probably graduate from playing the

video game Guitar Hero to actually learning to play guitar.* I bought an

acoustic guitar and started watching every beginning guitar instructional

video on YouTube. At first, the vocabulary the online guitar teachers used

was like a foreign language to me—terms like major and minor chords,

open G tuning, and circle of fifths. I was overwhelmed by how complicat-

ed it all was, and the fingertips on my left hand felt like they were going to

fall off from pressing on the steel strings on the neck of my guitar to form

* This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommer-

cial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) and are subject to the

Writing Spaces Terms of Use. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.

org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/, email info@creativecommons.org, or send a letter to Creative

Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042, USA. To view the Writing Spaces

Terms of Use, visit http://writingspaces.org/terms-of-use.

Understanding Discourse Communities 101

WRITING SPACES 3

chords. I felt like I was making incredibly slow progress, and at the rate

I was going, I wouldn’t be a guitar god until I was 87. I was also getting

tired of playing alone in my living room. I wanted to find a community of

people who shared my goal of learning songs and playing guitar together

for fun.

I needed a way to find other beginning and intermediate guitar play-

ers, and I decided to try a social media website called “Meetup.com.” It

only took a few clicks to find the right community for me—an “acoustic

jam” group that welcomed beginners and met once a month at a music

store near my city of Sacramento, California. On the Meetup.com site, it

said that everyone who showed up for the jam should bring a few songs to

share, but I wasn’t sure what kind of music they played, so I just showed up

at the next meet-up with my guitar and the basic look you need to become

a guitar legend: two days of facial hair stubble, black t-shirt, ripped jeans,

and a gravelly voice (luckily my throat was sore from shouting the lyrics to

the Twenty One Pilots song “Heathens” while playing guitar in my living

room the night before).

The first time I played with the group, I felt more like a junior high

school band camp dropout then the next Jimi Hendrix. I had trouble keep-

ing up with the chord changes, and I didn’t know any scales (groups of

related notes in the same key that work well together) to solo on lead guitar

when it was my turn. I had trouble figuring out the patterns for my strum-

ming hand since no one took the time to explain them before we started

playing a new song. The group had some beginners, but I was the least

experienced player.

It took a few more meet-ups, but pretty soon I figured out how to fit

into the group. I learned that they played all kinds of songs, from country

to blues to folk to rock music. I learned that they chose songs with simple

chords so beginners like me could play along. I learned that they brought

print copies of the chords and lyrics of songs to share, and if there were any

difficult chords in a song, they included a visual of the chord shape in the

handout of chords and lyrics. I started to learn the musician’s vocabulary I

needed to be familiar with to function in the group, like beats per measure

and octaves and the minor pentatonic scale. I learned that if I was having

trouble figuring out the chord changes, I could watch the better guitarists

and copy what they were doing. I also got good advice from experienced

players, like soaking your fingers in rubbing alcohol every day for ninety

seconds to toughen them up so the steel strings wouldn’t hurt as much. I

even realized that although I was an inexperienced player, I could contrib-

ute to the community by bringing in new songs they hadn’t played before.

Dan Melzer102

WRITING SPACES 3

Okay, at this point you may be saying to yourself that all of this will

make a great biographical movie someday when I become a rock icon (or

maybe not), but what does it have to do with becoming a better writer?

You can write in a journal alone in your room, just like you can play

guitar just for yourself alone in your room. But most writers, like most

musicians, learn their craft from studying experts and becoming part of a

community. And most writers, like most musicians, want to be a part of

community and communicate with other people who share their goals and

interests. Writing teachers and scholars have come up with the concept of

“discourse community” to describe a community of people who share the

same goals, the same methods of communicating, the same genres, and the

same lexis (specialized language).

What Exactly Is a Discourse Community?

John Swales, a scholar in linguistics, says that discourse communities have

the following features (which I’m paraphrasing):

1. A broadly agreed upon set of common public goals

2. Mechanisms of intercommunication among members

3. Use of these communication mechanisms to provide information

and feedback

4. One or more genres that help further the goals of the dis-

course community

5. A specific lexis (specialized language)

6. A threshold level of expert members (24-26)

I’ll use my example of the monthly guitar jam group I joined to explain

these six aspects of a discourse community.

A broadly Agreed Set of Common Public Goals

The guitar jam group had shared goals that we all agreed on. In the Meet-

up.com description of the site, the organizer of the group emphasized that

these monthly gatherings were for having fun, enjoying the music, and

learning new songs. “Guitar players” or “people who like music” or even

“guitarists in Sacramento, California” are not discourse communities.

They don’t share the same goals, and they don’t all interact with each other

to meet the same goals.

Understanding Discourse Communities 103

WRITING SPACES 3

Mechanisms of Intercommunication among Members

The guitar jam group communicated primarily through the Meetup.com

site. This is how we recruited new members, shared information about

when and where we were playing, and communicated with each other out-

side of the night of the guitar jam. “People who use Meetup.com” are not a

discourse community, because even though they’re using the same method

of communication, they don’t all share the same goals and they don’t all

regularly interact with each other. But a Meetup.com group like the Sac-

ramento acoustic guitar jam focused on a specific topic with shared goals

and a community of members who frequently interact can be considered a

discourse community based on Swales’ definition.

Use of These Communication Mechanisms

to Provide Information and Feedback

Once I found the guitar jam group on Meetup.com, I wanted information

about topics like what skill levels could participate, what kind of music

they played, and where and when they met. Once I was at my first gui-

tar jam, the primary information I needed was the chords and lyrics of

each song, so the handouts with chords and lyrics were a key means of

providing critical information to community members. Communication

mechanisms in discourse communities can be emails, text messages, social

media tools, print texts, memes, oral presentations, and so on. One reason

that Swales uses the term “discourse” instead of “writing” is that the term

“discourse” can mean any type of communication, from talking to writing

to music to images to multimedia.

One or More Genres That Help Further the

Goals of the Discourse Community

One of the most common ways discourse communities share information

and meet their goals is through genres. To help explain the concept of

genre, I’ll use music since I’ve been talking about playing guitar and music

is probably an example you can relate to. Obviously there are many types

of music, from rap to country to reggae to heavy metal. Each of these

types of music is considered a genre, in part because the music has shared

features, from the style of the music to the subject of the lyrics to the lexis.

For example, most rap has a steady bass beat, most rappers use spoken

word rather singing, and rap lyrics usually draw on a lexis associated with

young people. But a genre is much more than a set of features. Genres arise

out of social purposes, and they’re a form of social action within discourse

Dan Melzer104

WRITING SPACES 3

communities. The rap battles of today have historical roots in African oral

contests, and modern rap music can only be understood in the context of

hip hop culture, which includes break dancing and street art. Rap also has

social purposes, including resisting social oppression and telling the truth

about social conditions that aren’t always reported on by news outlets. Like

all genres, rap is not just a formula but a tool for social action.

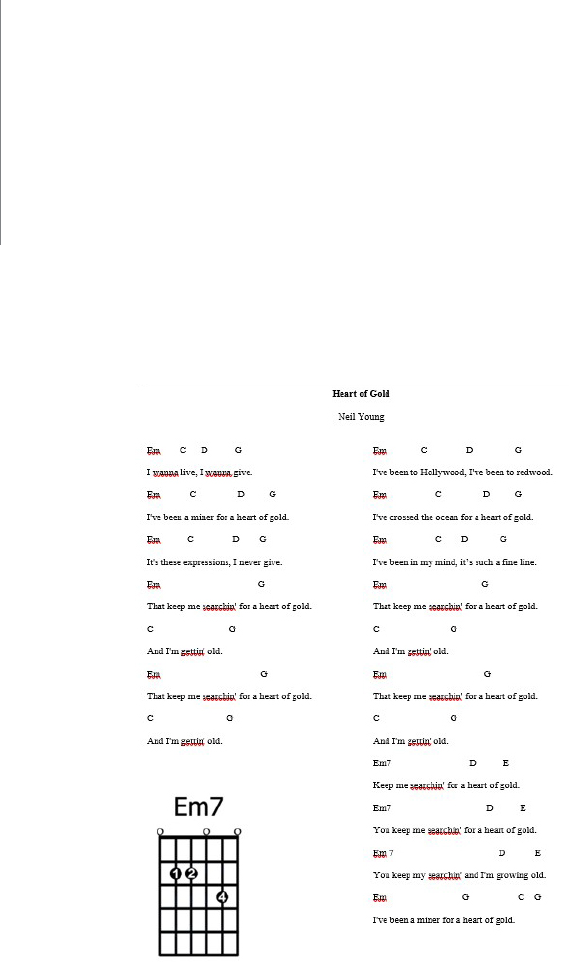

The guitar jam group used two primary genres to meet the goals of the

community. The Meetup.com site was one important genre that was crit-

ical in the formation of the group and to help it recruit new members. It

was also the genre that delivered information to the members about what

the community was about and where and when the community would

be meeting. The other important genre to the guitar jam group were the

handouts with song chords and lyrics. I’m sharing an example of a song I

brought to the group to show you what this genre looks like.

Figure 1: Lyrics and chord changes for “Heart of Gold” by Neil Young with a

fingering chart for an E minor 7 chord

Understanding Discourse Communities 105

WRITING SPACES 3

This genre of the chord and lyrics sheet was needed to make sure ev-

eryone could play along and follow the singer. The conventions of this

genre—the “norms”—weren’t just arbitrary rules or formulas. As with all

genres, the conventions developed because of the social action of the genre.

The sheets included lyrics so that we could all sing along and make sure

we knew when to change chords. The sheets included visuals of unusual

chords, like the Em7 chord (E minor seventh) in my example, because

there were some beginner guitarists who were a part of the community. If

the community members were all expert guitarists, then the inclusion of

chord shapes would never have become a convention. A great resource to

learn more about the concept of genre is the essay “Navigating Genres” by

Kerry Dirk in volume 1 of Writing Spaces.

A Specific Lexis (Specialized Language)

To anyone who wasn’t a musician, our guitar meet-ups might have sound-

ed like we were communicating in a foreign language. We talked about the

root note of scale, a 1/4/5 chord progression, putting a capo on different

frets, whether to play solos in a major or minor scale, double drop D tun-

ing, and so on. If someone couldn’t quickly identify what key their song

was in or how many beats per measure the strumming pattern required,

they wouldn’t be able to communicate effectively with the community

members. We didn’t use this language to show off or to try to discourage

outsiders from joining our group. We needed these specialized terms—this

musician’s lexis—to make sure we were all playing together effectively.

A Threshold Level of Expert Members

If everyone in the guitar jam was at my beginner level when I first joined

the group, we wouldn’t have been very successful. I relied on more ex-

perienced players to figure out strumming patterns and chord changes,

and I learned to improve my solos by watching other players use various

techniques in their soloing. The most experienced players also helped ed-

ucate everyone on the conventions of the group (the “norms” of how the

group interacted). These conventions included everyone playing in the

same key, everyone taking turns playing solo lead guitar, and everyone

bringing songs to play. But discourse community conventions aren’t always

just about maintaining group harmony. In most discourse communities,

new members can also expand the knowledge and genres of the commu-

nity. For example, I shared songs that no one had brought before, and that

expanded the community’s base of knowledge.

Dan Melzer106

WRITING SPACES 3

Why the Concept of Discourse Communities

Matters for College Writing

When I was an undergraduate at the University of Florida, I didn’t un-

derstand that each academic discipline I took courses in to complete the

requirements of my degree (history, philosophy, biology, math, political

science, sociology, English) was a different discourse community. Each of

these academic fields had their own goals, their own genres, their own

writing conventions, their own formats for citing sources, and their own

expectations for writing style. I thought each of the teachers I encountered

in my undergraduate career just had their own personal preferences that all

felt pretty random to me. I didn’t understand that each teacher was trying

to act as a representative of the discourse community of their field. I was

a new member of their discourse communities, and they were introduc-

ing me to the genres and conventions of their disciplines. Unfortunately,

teachers are so used to the conventions of their discourse communities that

they sometimes don’t explain to students the reasons behind the writing

conventions of their discourse communities.

It wasn’t until I studied research about college writing while I was in

graduate school that I learned about genres and discourse communities,

and by the time I was doing my dissertation for my PhD, I got so interested

in studying college writing that I did a national study of college teachers’

writing assignments and syllabi. Believe it or not, I analyzed the genres

and discourse communities of over 2,000 college writing assignments in

my book Assignments Across the Curriculum. To show you why the idea of

discourse community is so important to college writing, I’m going to share

with you some information from one of the academic disciplines I studied:

history. First I want to share with you an excerpt from a history course

writing assignment from my study. As you read it over, think about what

it tells you about the conventions of the discourse community of history.

Documentary Analysis

This assignment requires you to play the detective, combing textual sourc-

es for clues and evidence to form a reconstruction of past events. If you

took A.P. history courses in high school, you may recall doing similar doc-

ument-based questions (DBQs).

In a tight, well-argued essay of two to four pages, identify and assess

the historical significance of the documents in ONE of the four sets I have

given you.

Understanding Discourse Communities 107

WRITING SPACES 3

You bring to this assignment a limited body of outside knowledge

gained from our readings, class discussions, and videos. Make the most of

this contextual knowledge when interpreting your sources: you may, for

example, refer to one of the document from another set if it sheds light on

the items in your own.

Questions to Consider When Planning Your Essay

• What do the documents reveal about the author and his audience?

• Why were they written?

• What can you discern about the author’s motivation and tone? Is

the tone revealing?

• Does the genre make a difference in your interpretation?

• How do the documents fit into both their immediate and their

greater historical contexts?

• Do your documents support or contradict what other sources (vid-

eo, readings) have told you?

• Do the documents reveal a change that occurred over a period of

time?

• Is there a contrast between documents within your set? If so, how

do you account for it?

• Do they shed light on a historical event, problem, or period? How

do they fit into the “big picture”?

• What incidental information can you glean from them by reading

carefully? Such information is important for constructing a narra-

tive of the past; our medieval authors almost always tell us more

than they intended to.

• What is not said, but implied?

• What is left out? (As a historian, you should always look for what is

not said, and ask yourself what the omission signifies.)

• Taken together, do the documents reveal anything significant

about the period in question? (Melzer 3-4)

This assignment doesn’t just represent the specific preferences of one

random teacher. It’s a common history genre (the documentary analysis)

that helps introduce students to the ways of thinking and the communi-

cation conventions of the discourse community of historians. This genre

reveals that historians look for textual clues to reconstruct past events and

that historians bring their own knowledge to bear when they analyze texts

and interpret history (historians are not entirely “objective” or “neutral”).

Dan Melzer108

WRITING SPACES 3

In this documentary analysis genre, the instructor emphasizes that histori-

ans are always looking for what is not said but instead is implied. This in-

structor is using an important genre of history to introduce students to the

ways of analyzing and thinking in the discourse community of historians.

Let’s look at another history course in my research. I’m sharing with

you an excerpt from the syllabus of a history of the American West course.

This part of the syllabus gives students an overview of the purpose of the

writing projects in the class. As you read this overview, think about the

ways this instructor is portraying the discourse community of historians.

A300: History of the American West

A300 is designed to allow students to explore the history of the American

West on a personal level with an eye toward expanding their knowledge

of various western themes, from exploration to the Indian Wars, to the

impact of global capitalism and the emergence of the environmental move-

ment. But students will also learn about the craft of history, including the

tools used by practitioners, how to weigh competing evidence, and how to

build a convincing argument about the past.

At the end of this course students should understand that history is

socially interpreted, and that the past has always been used as an import-

ant means for understanding the present. Old family photos, a grandpar-

ent’s memories, even family reunions allow people to understand their lives

through an appreciation of the past. These events and artifacts remind

us that history is a dynamic and interpretive field of study that requires

far more than rote memorization. Historians balance their knowledge of

primary sources (diaries, letters, artifacts, and other documents from the

period under study) with later interpretations of these people, places, and

events (in the form of scholarly monographs and articles) known as sec-

ondary sources. Through the evaluation and discussion of these different

interpretations historians come to a socially negotiated understanding of

historical figures and events.

Individual Projects

More generally, your papers should:

1. Empathize with the person, place, or event you are writing about.

The goal here is to use your understanding of the primary and

secondary sources you have read to “become” that person–i.e. to

appreciate their perspectives on the time or event under study. In

Understanding Discourse Communities 109

WRITING SPACES 3

essence, students should demonstrate an appreciation of that time

within its context.

2. Second, students should be able to present the past in terms of its

relevance to contemporary issues. What do their individual proj-

ects tell us about the present? For example, what does the treatment

of Native Americans, Mexican Americans, and Asian Americans

in the West tell us about the problem of race in the United States

today?

3. Third, in developing their individual and group projects, students

should demonstrate that they have researched and located primary

and secondary sources. Through this process they will develop the

skills of a historian, and present an interpretation of the past that is

credible to their peers and instructors.

Just like the history instructor who gave students the documentary anal-

ysis assignment, this history of the American West instructor emphasizes

that the discourse community of historians doesn’t focus on just memoriz-

ing facts, but on analyzing and interpreting competing evidence. Both the

documentary analysis assignment and the information from the history of

the American West syllabus show that an important shared goal of the dis-

course community of historians is socially constructing the past using ev-

idence from different types of artifacts, from texts to photos to interviews

with people who have lived through important historical events. The dis-

course community goals and conventions of the different academic disci-

plines you encounter as an undergraduate shape everything about writing:

which genres are most important, what counts as evidence, how arguments

are constructed, and what style is most appropriate and effective.

The history of the American West course is a good example of the

ways that discourse community goals and values can change over time. It

wasn’t that long ago that American historians who wrote about the West

operated on the philosophy of “manifest destiny.” Most early historians of

the American West assumed that the American colonizers had the right to

take land from indigenous tribes—that it was the white European’s “des-

tiny” to colonize the American West. The evidence early historians used

in their writing and the ways they interpreted that evidence relied on the

perspectives of the “settlers,” and the perspectives of the indigenous peo-

ple were ignored by historians. The concept of manifest destiny has been

strongly critiqued by modern historians, and one of the primary goals of

most modern historians who write about the American West is to recover

the perspectives and stories of the indigenous peoples as well as to continue

Dan Melzer110

WRITING SPACES 3

to work for social justice for Native Americans by showing how historical

injustices continue in different forms to the present day. Native Ameri-

can historians are now retelling history from the perspective of indigenous

people, using indigenous research methods that are often much differ-

ent than the traditional research methods of historians of the American

West. Discourse community norms can silence and marginalize people,

but discourse communities can also be transformed by new members who

challenge the goals and assumptions and research methods and genre con-

ventions of the community.

Discourse Communities from School

to Work and Beyond

Understanding what a discourse community is and the ways that genres

perform social actions in discourse communities can help you better un-

derstand where your college teachers are coming from in their writing as-

signments and also help you understand why there are different writing

expectations and genres for different classes in different fields. Researchers

who study college writing have discovered that most students struggle with

writing when they first enter the discourse community of their chosen ma-

jor, just like I struggled when I first joined the acoustic guitar jam group.

When you graduate college and start your first job, you will probably also

find yourself struggling a bit with trying to learn the writing conventions

of the discourse community of your workplace. Knowing how discourse

communities work will not only help you as you navigate the writing as-

signed in different general education courses and the specialized writing

of your chosen major, but it will also help you in your life after college.

Whether you work as a scientist in a lab or a lawyer for a firm or a nurse

in a hospital, you will need to become a member of a discourse commu-

nity. You’ll need to learn to communicate effectively using the genres of

the discourse community of your workplace, and this might mean asking

questions of more experienced discourse community members, analyzing

models of the types of genres you’re expected to use to communicate, and

thinking about the most effective style, tone, format, and structure for

your audience and purpose. Some workplaces have guidelines for how to

write in the genres of the discourse community, and some workplaces will

initiate you to their genres by trial and error. But hopefully now that you’ve

read this essay, you’ll have a better idea of what kinds of questions to ask to

help you become an effective communicator in a new discourse communi-

ty. I’ll end this essay with a list of questions you can ask yourself whenever

Understanding Discourse Communities 111

WRITING SPACES 3

you’re entering a new discourse community and learning the genres of

the community:

1. What are the goals of the discourse community?

2. What are the most important genres community members use to

achieve these goals?

3. Who are the most experienced communicators in the dis-

course community?

4. Where can I find models of the kinds of genres used by the dis-

course community?

5. Who are the different audiences the discourse community com-

municates with, and how can I adjust my writing for these differ-

ent audiences?

6. What conventions of format, organization, and style does the dis-

course community value?

7. What specialized vocabulary (lexis) do I need to know to commu-

nicate effectively with discourse community insiders?

8. How does the discourse community make arguments, and what

types of evidence are valued?

9. Do the conventions of the discourse community silence any mem-

bers or force any members to conform to the community in ways

that make them uncomfortable?

10. What can I add to the discourse community?

Works Cited

Dirk, Kerry. “Navigating Genres.” Writing Spaces, vol. 1, edited by Charles Lowe

and Pavel Zemliansky, Parlor Press, 2010, pp. 249–262.

Guitar Hero. Harmonics, 2005.

Meetup.com. WeWork Companies Inc., 2019. www.meetup.com.

Melzer, Daniel. Assignments Across the Curriculum: A National Study of College

Writing. Logan, UT: Utah State UP, 2014.

Swales, John. Genre Analysis: English in Academic and Research Settings. Boston:

Cambridge UP, 1990.

Twenty One Pilots. “Heathens.” Suicide Squad: The Album, Atlantic Re-

cords, 2016.

Young, Neil. “Heart of Gold.” Harvest, Reprise Records, 1972.

Dan Melzer112

WRITING SPACES 3

Teacher Resources for Understanding

Discourse Communities by Dan Melzer

Overview and Teaching Strategies

This essay can be taught in conjunction with teaching students about the

concept of genre and could be paired with Kerry Dirk’s essay “Navigating

Genres” in Writing Spaces, volume 1. I find that it works best to scaffold

the concept of discourse community by moving students from reflecting

on the formulaic writing they have learned in the past, like the five-para-

graph theme or the Shaffer method, to introducing them to the concept

of genre and how genres are not formulas or formats but forms of social

action, and then to helping students understand that genres usually op-

erate within discourse communities. Most of my students are unfamiliar

with the concept of discourse community, and I find that it is helpful to

relate this concept to discourse communities students are already members

of, like online gaming groups, college clubs, or jobs students are working

or have worked. I sometimes teach the concept of discourse community as

part of a research project where students investigate the genres and com-

munication conventions of a discourse community they want to join or

are already a member of. In this project students conduct primary and sec-

ondary research and rhetorically analyze examples of the primary genres

of the discourse community. The primary research might involve doing an

interview or interviews with discourse community members, conducting a

survey of discourse community members, or reflecting on participant-ob-

server research.

Inevitably, some students have trouble differentiating between a dis-

course community and a group of people who share similar characteristics.

Students may assert that “college students” or “Facebook users” or “teenage

women” are a discourse community. It is useful to apply Swales’ criteria to

broader groups that students imagine are discourse communities and then

try to narrow down these groups until students have hit upon an actual

discourse community (for example, narrowing from “Facebook users” to

the Black Lives Matter Sacramento Facebook group). In the essay, I tried to

address this issue with specific examples of groups that Swales would not

classify as a discourse community.

Teaching students about academic discourse communities is a chal-

lenging task. Researchers have found that there are broad expectations for

writing that seem to hold true across academic discourse communities,

such as the ability to make logical arguments and support those arguments

Understanding Discourse Communities 113

WRITING SPACES 3

with credible evidence, the ability to use academic vocabulary and write

in a formal style, and the ability to carefully edit for grammar, syntax, and

citation format. But research has also shown that not only do different ac-

ademic fields have vastly different definitions of how arguments are made,

what counts as evidence, and what genres, styles, and formats are valued,

but even similar types of courses within the same discipline may have very

different discourse community expectations depending on the instructor,

department, and institution. In teaching students about the concept of dis-

course community, I want students to leave my class understanding that: a)

there is no such thing as a formula or set of rules for “academic discourse”;

b) each course in each field of study they take in college will require them

to write in the context of a different set of discourse community expec-

tations; and c) discourse communities can both pass down community

knowledge to new members and sometimes marginalize or silence mem-

bers. What I hope students take away from reading this essay is a more

rhetorically sophisticated and flexible sense of the community contexts of

the writing they do both in and outside of school.

Questions

1. The author begins the essay discussing a discourse community he

has recently become a member of. Think of a discourse community

that you recently joined and describe how it meets Swales’ criteria

for a discourse community.

2. Choose a college class you’ve taken or are taking and describe the

goals and expectations for writing of the discourse community the

class represents. In small groups, compare the class discourse com-

munity you described with two of your peers’ courses. What are

some of the differences in the goals and expectations for writing?

3. Using Swales’ criteria for a discourse community, consider whether

the following are discourse communities and why or why not: a)

students at your college; b) a fraternity or sorority; c) fans of soccer;

d) a high school debate team.

4. The author of this essay argues that discourse communities use

genres for social actions. Consider your major or a field you would

like to work in after you graduate. What are some of the most

important genres of that discourse community? In what ways do

these genres perform social actions for members of the discourse

community?

Dan Melzer114

WRITING SPACES 3

Activities

The following are activities that can provide scaffolding for a discourse

community analysis project. To view example student discourse communi-

ty analysis projects from the first-year composition program that I direct at

the University of California, Davis, see our online student writing journal

at fycjournal.ucdavis.edu.

Introducing the Concept of Discourse Community

To introduce students to the concept of discourse community, I like to start

with discourse communities they can relate to or that they themselves are

members of. A favorite example for my students is the This American Life

podcast episode that explores the Instagram habits of teenage girls, which

can be found at https://www.thisamericanlife.org/573/status-update. Oth-

er examples students can personally connect to include Facebook groups,

groups on the popular social media site Reddit, fan clubs of musical artists

or sports teams, and campus student special interest groups. Once we’ve

discussed a few examples of discourse communities they can relate to on a

personal level, I ask them to list some of the discourse communities they

belong to and we apply Swales’ criteria to a few of these examples as a class.

Genre Analysis

One goal of my discourse community analysis project is to help students

see the relationships between genres and the broader community contexts

that genres operate in. However, thinking of writing in terms of genre and

discourse community is a new approach for most of my students, and I

provide them with heuristic questions they can use to analyze the primary

genres of the discourse community they are focusing on in their projects.

These questions include:

1. Who is the audience(s) for the genre, and how does audience shape

the genre?

2. What social actions does the genre achieve for the dis-

course community?

3. What are the conventions of the genre?

4. How much flexibility do authors have to vary the conventions of

the genre?

5. Have the conventions of the genre changed over time? In what

ways and why?

Understanding Discourse Communities 115

WRITING SPACES 3

6. To what extent does the genre empower members of the discourse

community to speak, and to what extent does the genre marginal-

ize or silence members of the discourse community?

7. Where can a new discourse community member find models of

the genre?

Research Questions about the Discourse Community

You could choose to have the focus of students’ discourse community

projects be as simple as arguing that the discourse community they chose

meets Swales’ criteria and explaining why. If you want students to dig a lit-

tle deeper, you can ask them to come up with research questions about the

discourse community they are analyzing. For example, students can ask

questions about how the genres of the discourse community achieve the

goals of the community, or how the writing conventions of the discourse

community have changed over time and why they have changed, or how

new members are initiated to the discourse community and the extent to

which that initiation is effective. Some of my students are used to being

assigned research papers in school that ask them to take a side on a pro/

con issue and develop a simplistic thesis statement that argues for that po-

sition. In the discourse community analysis project, I push them to think

of research as more sophisticated than just taking a position and forming

a simplistic thesis statement. I want them to use primary and secondary

research to explore complex research questions and decide which aspects of

their data and their analysis are the most interesting and useful to report

on in their projects.