RESEARCH

Financial Benchmarks

for Direct-Market

Vegetable Farms

2021 Report

Franklin Egan, Sarah Bay Nawa

Study Contributors

Thank you to the 39 farmers who contributed

their time, insights, and data to this study.

John Hendrickson, Brad Barham, and Matthew Klein

(University of Wisconsin) helped design our survey

instrument and analyze data.

This study was initially made possible with generous

investments from Lady Moon Farms, the Jerry Brunetti

family, the Shon Seeley family, and more than 120

private donors.

Additional support was provided by a Pennsylvania

Department of Agriculture Specialty Crop Block

Grant and a Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture

Research Grant.

Report Contributors

Authors: Franklin Egan, Sarah Bay Nawa

Reviewers: John Hendrickson (University of Wisconsin);

William Kitsch (Ephrata National Bank); Elaine Lemmon

(Kitchen Table Consultants); Hannah Smith-Brubaker

(Pasa Sustainable Agriculture)

Editor: Melissa Cipollone

Proofreader: Marie Hathaway

Layout: Matt Todd

© Pasa Sustainable Agriculture. All rights reserved.

This report is available on Pasa’s website at

pasafarming.org/nancial-benchmarks-2021.

For more information about this report, contact

research@pasafarming.org.

Pasa Sustainable Agriculture cultivates environmentally

sound, economically viable, community-focused farms

and food systems.

Executive summary 4

Introduction 6

Participating farms 7

Methods 9

Benchmarks 10

Vegetable enterprise benchmarks 10

Farm business benchmarks 15

Insights 18

Trends: 2017–19 23

Three pathways to higher incomes 25

Public support for fair farm incomes 27

Conclusion 28

References 30

Contents

4 | FINANCIAL BENCHMARKS FOR DIRECT-MARKET VEGETABLE FARMS

Executive summary

Direct-market vegetable farming—where farmers sell their produce through

farmers markets, community supported agriculture (CSA) programs, on-farm

stores, and direct wholesale—is a growing sector of the agricultural economy

in the Mid-Atlantic region and nationally. Yet despite its popularity among both

farmers and eaters, there is little information available to help farmers start

and grow successful direct-market businesses.

In2017welaunchedanongoingstudytohelpllthiscriticalgapin

information and provide insights that could help vegetable farmers start and

growsuccessfulbusinesses.Wecompiledcustomnancialbenchmarkreports

for each farm participating in the study, and we hosted meetings where

participantscouldshareanddiscusstheirbusinessnancesopenly.

Thisreportsharesdetailednancialbenchmarksandinsightsfromthe39

vegetable farms that participated in our study. These farms were all located

in four Mid-Atlantic states (Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virgina, West Virginia) and

sold some or all of their produce through direct-market channels during tax

years 2017 through 2019. We also share trends over time for a subset of 19

farms that participated in our study all three years. Lastly, we explore strategies

farmers can use to improve their direct-market income, and consider how

publicpolicycansupportthelong-termnancialviabilityoftheseessential

businesses.

To our knowledge, this report is the most comprehensive review of direct-

marketvegetablefarmbusinessmodelsproducedtodate.Ourndings

include:

• Most direct-market vegetable farmers are not earning a middle-

class income. A quarter of farms in our study earned more than the

Pennsylvania median household income. Most, though, had a median net

farm income that was less than half the Pennsylvania median for all farms.

• No single direct-market channel outperformed all others. We found

that all of the major direct-market channels used by farms in our study—

farmers markets, CSAs, direct wholesale—had a mix of higher and lower

income cases.

• Larger production scales bring higher incomes. Farms in our study with

more acres in vegetable production generally realized higher net incomes

than farms with less acres in vegetable production.

PASA SUSTAINABLE AGRICULTURE | 5

• Farms that focus on vegetables make more money on vegetables—

but may miss out on higher net incomes from other enterprises.

We found that farms in our study operating enterprises beyond solely

marketing vegetables grown on their farms had higher net farm incomes.

This was especially true for farms that resold products from other farms.

• Farms steadily increased incomes and equity over time. Farms in our

studygenerallybecomemoreprotablethelongertheywereinbusiness.

Most farms exceeded the Pennsylvania median household income

within12yearsofbusiness,whileaccumulatingsignicantwealthinland,

buildings, and equipment assets.

• There are three major pathways to make more money growing

vegetables. Our data point to expanding production scale, increasing

revenueperacre,orimprovingcostandlaborefciencyasthetopthree

strategies for increasing direct-market vegetable income.

• The nancial benchmarks presented in this report are consistent with

persistent structural challenges in the agricultural industry. Creating

and expanding public programs is necessary to help direct-market

vegetable farmers continue their essential work providing fresh, nutritious

food for their communities.

• Farmers value sharing and discussing nancial data. Most farmers

participating in our study found the insights they received and the

opportunitiestodiscusstheirbusinessnanceswithotherfarmers

in a safe environment highly valuable.

Our Direct Market Benchmark Study is an ongoing project. Since compiling the

ndingsdetailedinthisreport,we’vepartneredwithpeerorganizationsinNew

England (Community Involved in Sustainable Agriculture) and the Carolinas

(Carolina Farm Stewardship Association) to expand the scope of our study to

include data from vegetable farms located outside of the Mid-Atlantic region.

We will also be analyzing the impact the COVID-19 pandemic has had on

participating farms in a future report.

GET INVOLVED: If you own or manage a vegetable farm that sells some or

all of your products through direct market channels, we welcome you to join

our ongoing study. Learn more at pasafarming.org/research or contact us

at research@pasafarming.org to get involved.

6 | FINANCIAL BENCHMARKS FOR DIRECT-MARKET VEGETABLE FARMS

Introduction

Farmers markets, community supported agriculture (CSA) programs, farm

stands, and direct wholesales to grocery stores, restaurants, and institutions

are sales channels that have long been cornerstones of the sustainable

agriculture movement in Pennsylvania and across the U.S. By building in-person

relationships with customers and garnering price premiums for fresher, higher

quality, and more sustainably grown produce, direct-market vegetable farms

have carved out an important niche in the modern agricultural industry. The

National Agricultural Statistics Service (2016) estimates that direct-market

farms generate $439 million in sales per year in Pennsylvania, with much of this

business coming from vegetables.

1

Direct-market farming has provided an on-ramp into farming careers for

many beginning farmers and supplied communities with better access to fresh,

nutritious food. Direct-market farms have also pioneered sustainable growing

techniques that rely on biodiversity to build soils and control pests. Yet, despite

the big-picture success of direct-market business models, there is surprisingly

little information available to help current or aspiring farmers answer a very

basic question: Can farmers make a middle-class income selling vegetables

through direct-market outlets?

Thisreportcontributestoaverysmallsetofresourcesexploringnances

for direct-market vegetable farms. Existing resources on this topic include

data compiled by Practical Farmers of Iowa and the Center for Integrated

Agricultural Systems.

2,3

Our data set also expands on existing resources by

including a range of variables describing each participating farm’s market

channels, production scale, level of diversity and specialization, and years of

farming experience. This allows us to provide a uniquely detailed look at some

ofthekeyfactorsshapingnancialoutcomesfordirect-marketfarms.

Despite the big-picture success of direct-market business

models, there is surprisingly little information available

to help current or aspiring farmers answer a very basic

question: Can farmers make a middle-class income selling

vegetables through direct-market outlets?

“

PASA SUSTAINABLE AGRICULTURE | 7

Participating farms

Since the fall of 2017, we have recruited 39 farms in Pennsylvania, Maryland,

Virginia, and West Virginia to participate in our Direct Market Financial

Benchmarks Study (Table 1). All eligible farms needed to be for-prot

commercial operations and generate a signicant portion of their revenue

through direct-market sales of produce grown on the farm.

TABLE 1. PARTICIPATING FARMS BY YEAR

Year Number of farms

2017 36

2018 32

2019 23

Total 39

Of the farms that participated in our study in 2017, 81% returned for 2018,

with several additional farms joining the project that year. Participation declined

in2019,asmanyfarmsfounditdifculttosubmittheirdatainthespringof

2020 when the COVID-19 pandemic erupted.

We sought out candidate farms through our email newsletter; exhibiting and

presenting at farm conferences and events; and by advertising in various trade

publications.

Participating farms typically managed a range of enterprises, including

growing vegetables, reselling products grown or raised on other farms, and

hosting on-farm events and agritourism. Farms were located in peri-urban and

rural areas, and spanned a range of production scales from less than an acre

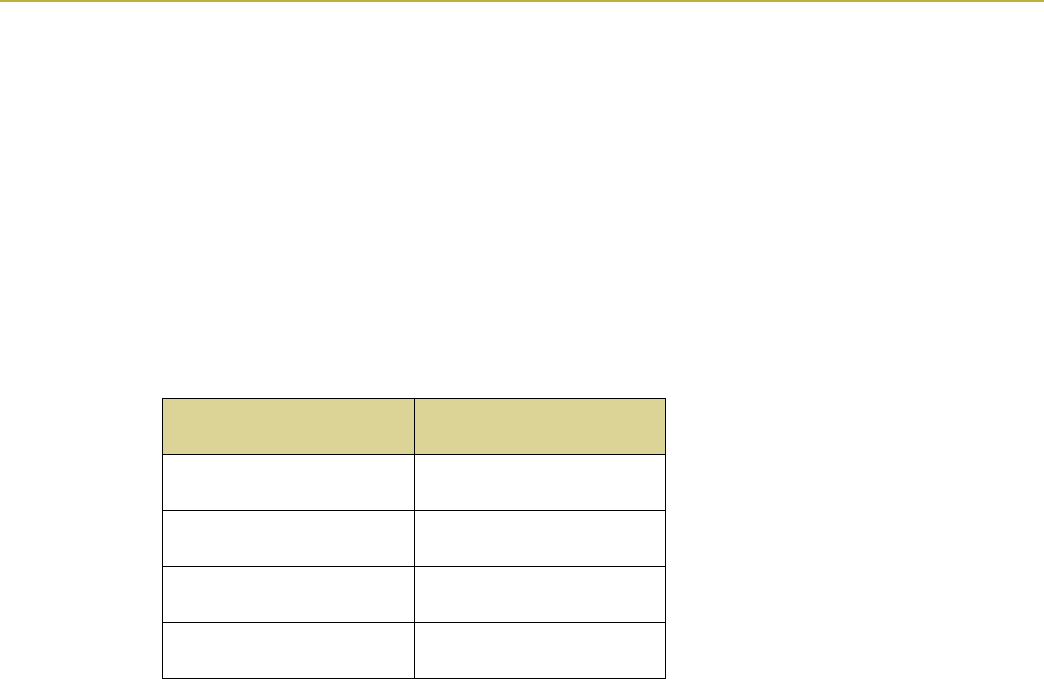

in vegetable production to more than 90 acres (Figure 1). Participating farmers

also had an assortment of experience levels, ranging from new start-ups to

decades in business (Figure 2). Just under half of participating farms primarily

leased or rented their farmland. Land ownership was more common among

larger farms, with all farms that had more than 12 acres in vegetable production

primarily owning their farmland (Figure 3).

8 | FINANCIAL BENCHMARKS FOR DIRECT-MARKET VEGETABLE FARMS

FIGURE 1. ACRES IN VEGETABLE PRODUCTION

>12 acres (15%)

3–12 acres (64%)

<3 acres (21%)

FIGURE 3. LAND TENURE

Owned land (53%)

Leased or rented land (47%)

FIGURE 2. YEARS OF FARMING EXPERIENCE

Includes experience as farm managers and farm workers

>25 years (18%)

10–25 years (59%)

5–10 years (21%)

<5 years (2%)

PASA SUSTAINABLE AGRICULTURE | 9

Methods

Over the winter months of 2018, 2019, and 2020 we coordinated a series

of in-person and virtual work sessions to help farmers complete a detailed

surveyregardingtheirfarmnancesforthe2017,2018,and2019taxyears.

We developed our survey with support from educators at the University of

Wisconsin, building on a survey they had shared with similar farms in Wisconsin.

Farmers were offered a $100 stipend for completing a survey for each tax year.

Our survey required farmers to draw information from their crop plans,

annualprot-and-lossstatements,ScheduleFtaxformorsimilartax

documents, and business balance sheets. We reviewed each survey carefully,

typically following up with farmers to clarify any ambiguities or inconsistencies

in their responses. As a result, we have a “carrots-to-carrots” dataset for which

we normalized different approaches to bookkeeping among different farm

business models.

Many of the farmers contributing to this project manage multiple

enterprises, including vegetables, livestock, fruit, and resale of products from

other farms. In order to make balanced comparisons, this report presents

benchmarks for each farm’s vegetable enterprise as well as their farm

business as a whole.

Our vegetable enterprise benchmarks refer to the production and

marketing of vegetables grown on each farm (this does not include any

resaleproducts).Ourdenitionofvegetablesforthepurposeofthisstudy

includes melons, herbs, strawberries, and other specialty crops often grown

ondiversiedvegetablefarms.Ourdenitiondoesnotincludeperennialfruit

trees,perennialberries,cutowers,ornurseryorbeddingplants.Farmers

reported vegetable sales by distinct market channels, including farmers

markets, CSA programs, and direct wholesale to restaurants, institutions, and

grocery stores. Many direct-market farms also use intermediary wholesale

channels such as produce auctions, food service companies, and marketing

co-ops.

Our farm business benchmarks refer to all of a farm’s agricultural

enterprises—including vegetables, resale products, nursery plants, livestock,

and agritourism or on-farm events—viewed as a combined business.

We used this data to calculate a series of standard business benchmarks for

each farm’s vegetable enterprise and for their farm business as a whole. We

also explored correlations between benchmark indicators and key aspects of

the farm business model and context, including market channels, production

scale, farmer experience, and enterprise diversity.

10 | FINANCIAL BENCHMARKS FOR DIRECT-MARKET VEGETABLE FARMS

Benchmarks

Thissectionreviewsthenancialbenchmarksachieved

by the 39 vegetable farms that participated in our

study between tax years 2017 and 2019. Each table

represents a combined average for these three years.

We segmented each benchmark by farm scale, so

you can see values for farms with less than three acres

in vegetable production (21% of participants), farms

with more than 12 acres in vegetable production (15%

of participants), and those that fall in between (64% of

participants).

VEGETABLE ENTERPRISE BENCHMARKS

The benchmarks in this section apply to vegetables produced on and marketed by a farm.

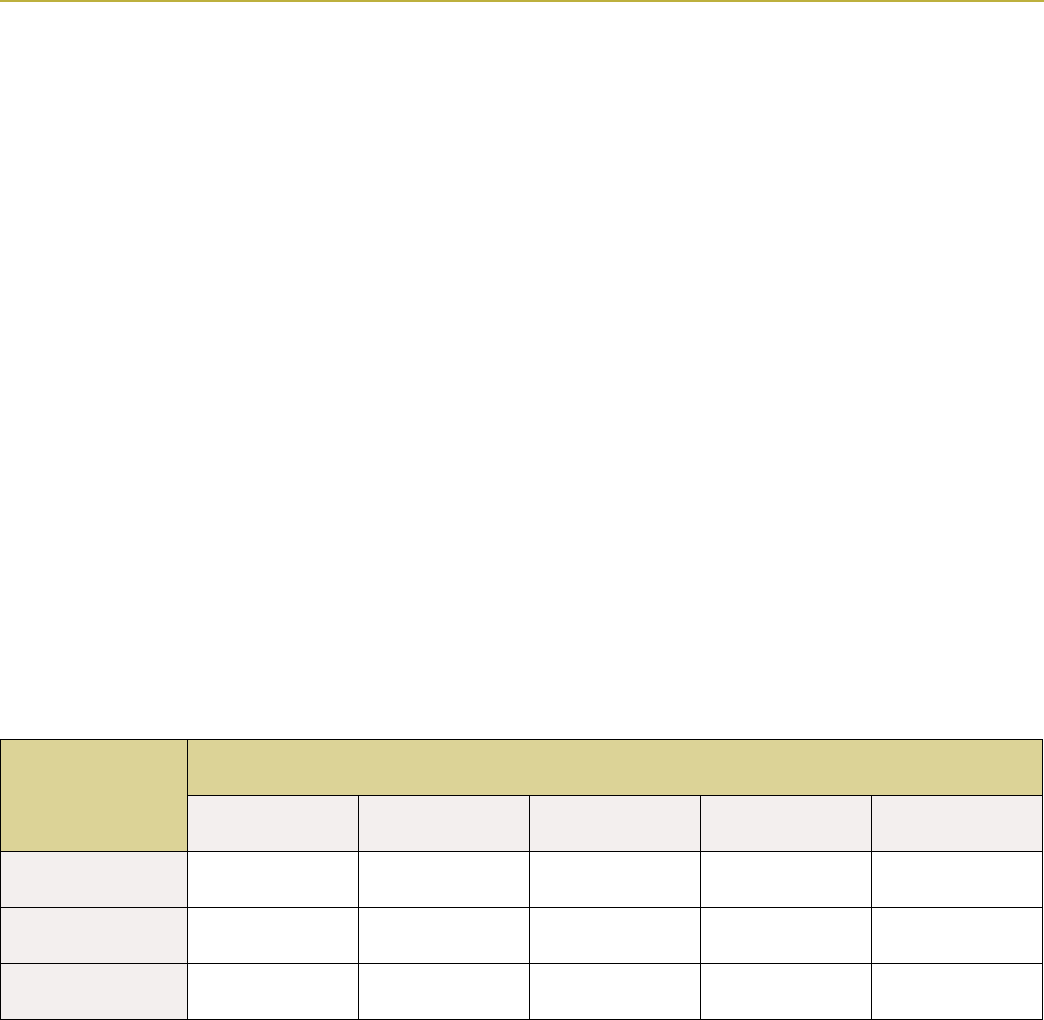

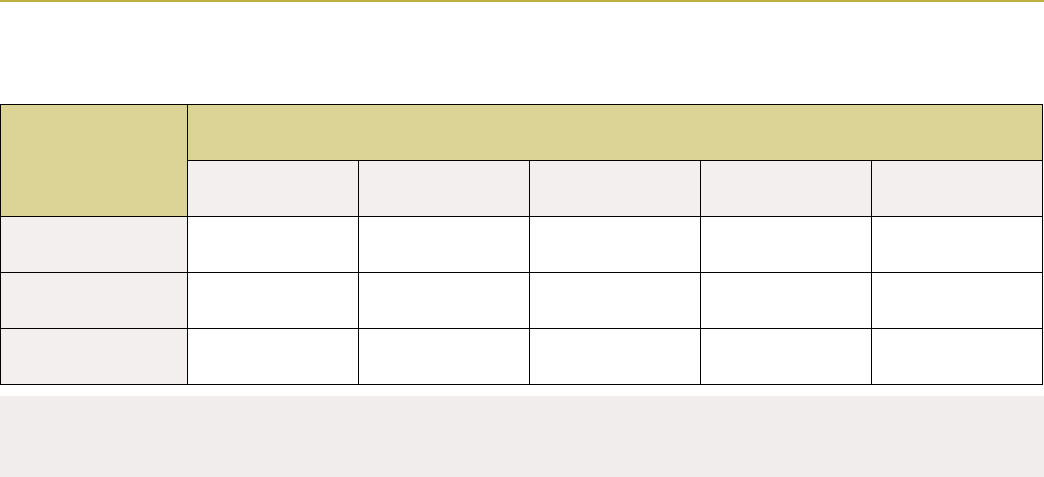

TABLE 2. GROSS VEGETABLE ENTERPRISE REVENUE

Scale

Percentile

10 25 median 75 90

< 3 acres $17, 264 $41,844 $64,704 $82,260 $114,761

3–12 acres $32,752 $44,543 $92,030 $140,370 $218,435

> 12 acres $ 457,58 4 $464,974 $488,773 $606,969 $750,297

Gross vegetable enterprise revenue measures the total sales revenue of

vegetables grown on a farm through all market channels combined. This may

include farmers markets, CSAs, on-farm stores, direct wholesale to restaurants,

grocery stores, and institutions, and wholesale through intermediaries.

For each benchmark, we show the 10, 25, median

(50), 75, and 90 percentile value. For example, as shown

in Table 2, the 25th percentile value for gross vegetable

enterprise revenue was $41,844 for farms with less than

three acres in vegetable production. That means that

25% of farms of this scale sold on average less than

$41,844 during tax years 2017–19.

PASA SUSTAINABLE AGRICULTURE | 11

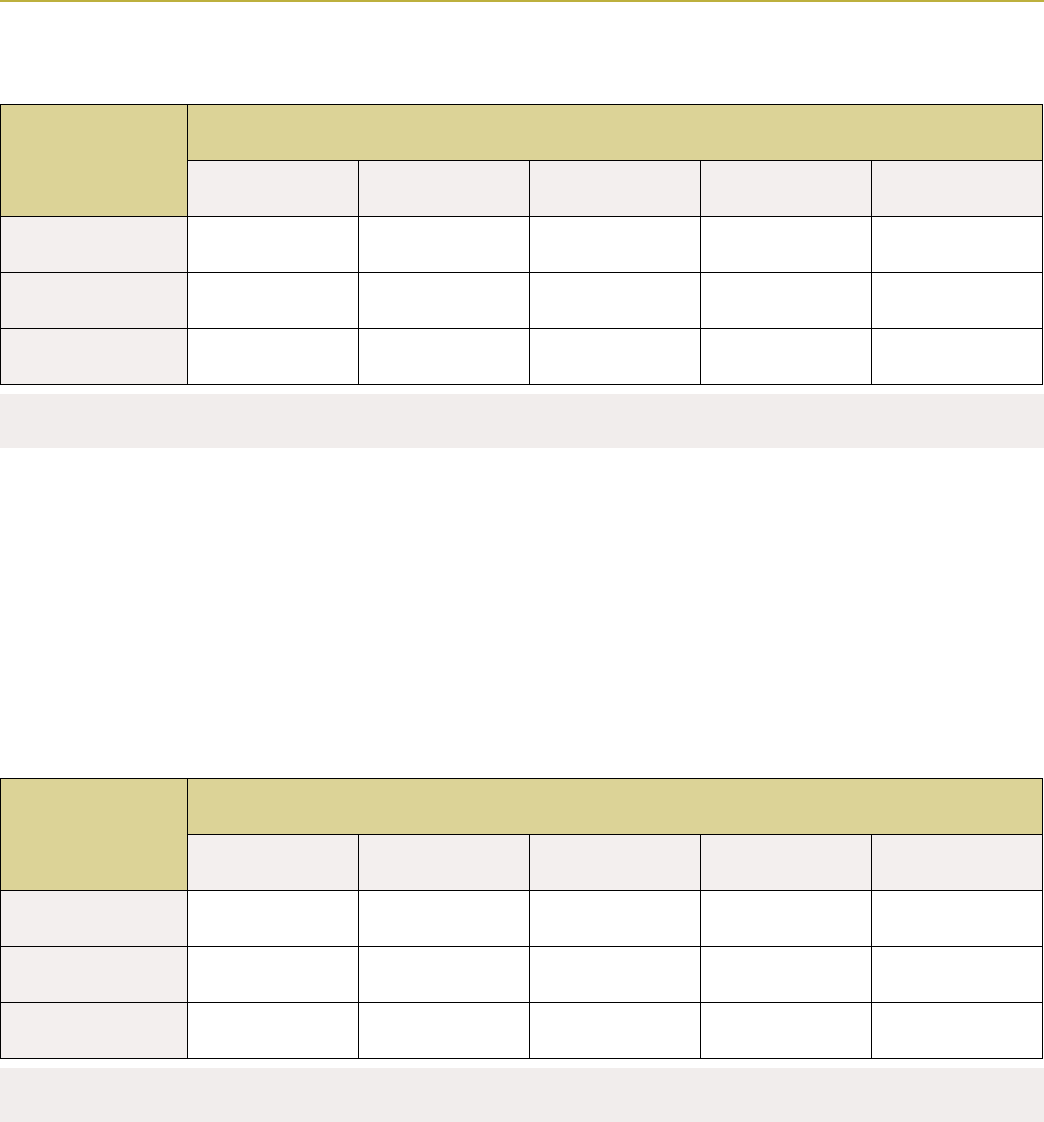

TABLE 3. GROSS VEGETABLE ENTERPRISE REVENUE PER ACRE

Scale

Percentile

10 25 median 75 90

< 3 acres $19,882 $27, 032 $46,413 $56,193 $64,820

3–12 acres $8,393 $11,223 $20,655 $29,194 $33,565

> 12 acres $11,600 $20,854 $23,250 $33,834 $35,342

= gross vegetable enterprise revenue / acres in vegetable production

Gross vegetable enterprise revenue per acre measures the intensity of an

operation—in other words, it shows how much revenue a vegetable enterprise

generatesperacre.Highervaluescanreectcombinationsofmoreproductive

soil, better marketing opportunities, or more intensive management systems.

Acres in vegetable production includes only acres that were used for

vegetable production for at least part of the year. It does not include farm lanes

or acres that were in full-season cover crops or short-term fallow.

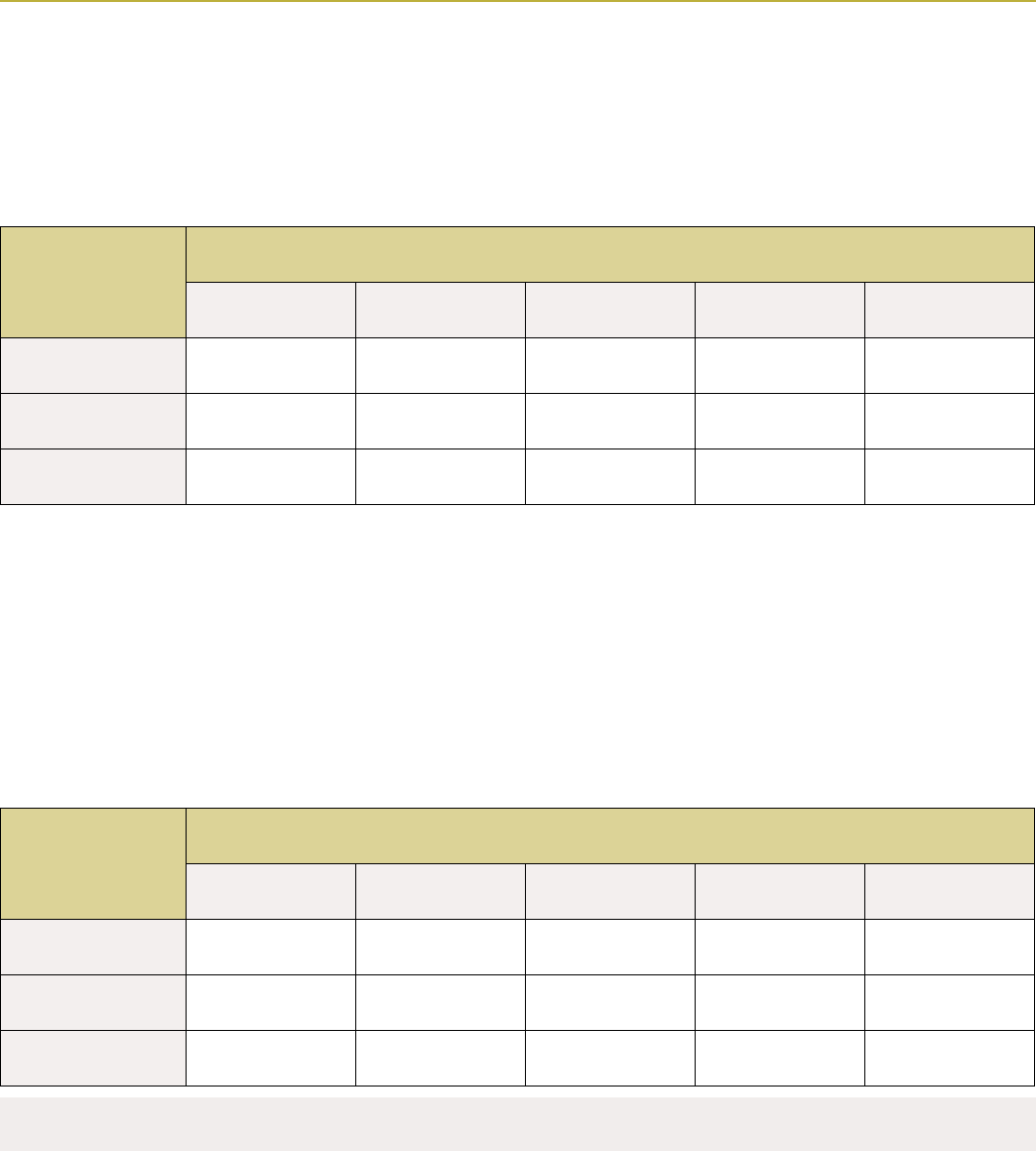

TABLE 4. VEGETABLE ENTERPRISE NET INCOME

Scale

Percentile

10 25 median 75 90

< 3 acres -$8,764 $77 $1,844 $6,435 $8,684

3–12 acres -$27,064 -$5,216 $12,079 $30,825 $53,096

> 12 acres $54,052 $74,207 $86,964 $116,079 $161,947

= gross vegetable enterprise revenue – vegetable enterprise operating expenses

Vegetable enterprise net income shows the total income generated by a

vegetable enterprise that is available to compensate salaries for farm owners,

or to make capital investments in the operation.

Ourdenitionofoperatingexpensesincludesallproductionandmarketing

costs for vegetables grown on a farm, including paid labor, land rental costs,

andmortgageinterestpayments.Ourdenitionofoperatingcostsdoesnot

include salaries for farm owners or business partners.

12 | FINANCIAL BENCHMARKS FOR DIRECT-MARKET VEGETABLE FARMS

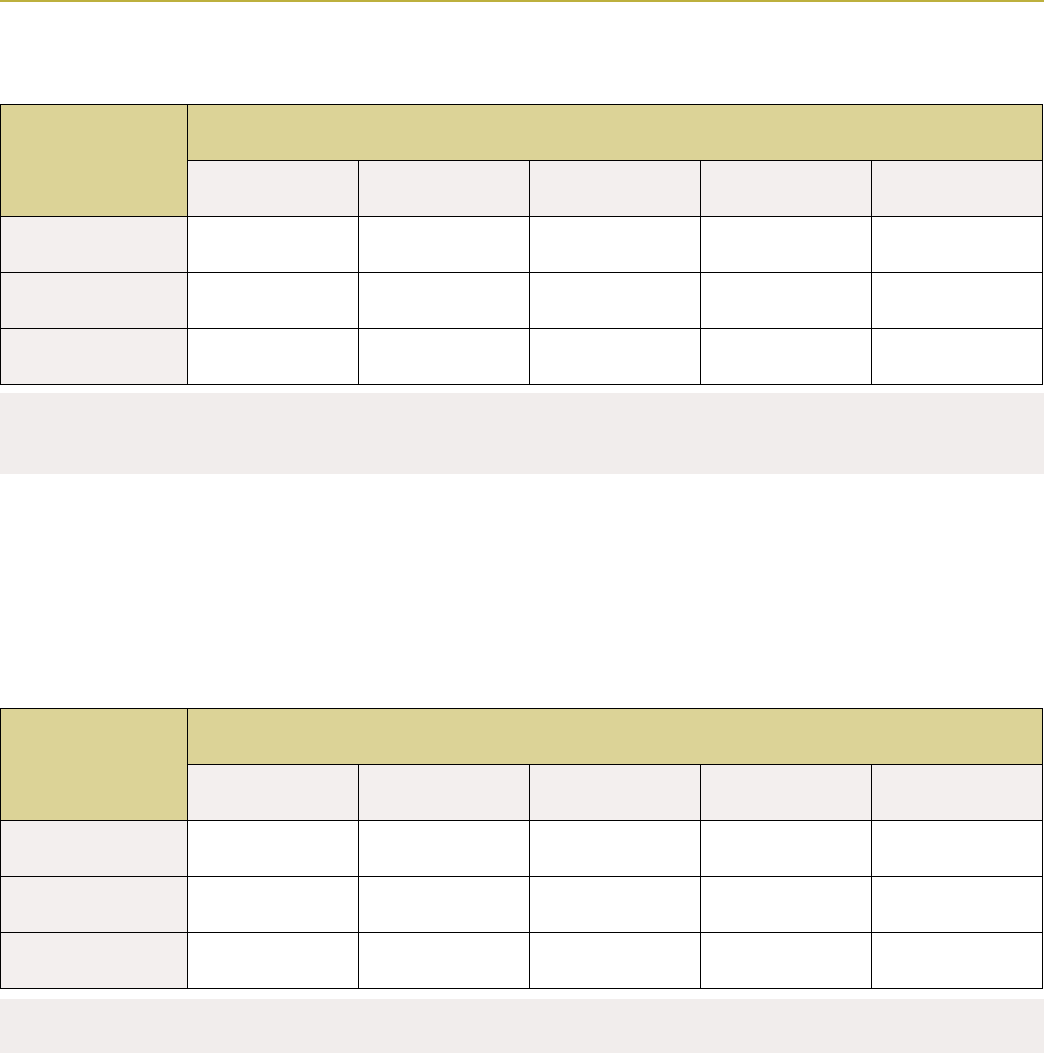

TABLE 5. NET INCOME PER ACRE IN VEGETABLES

Scale

Percentile

10 25 median 75 90

< 3 acres -$4,310 -$101 $2,163 $2,901 $8,180

3–12 acres - $ 7, 337 -$1,166 $2,890 $6,464 $9,094

> 12 acres $1,950 $2,139 $2,968 $3,232 $7, 016

= (gross vegetable enterprise revenue – vegetable enterprise operating expenses) /

acres in vegetable production

Net income per acre in vegetables shows what a farm earns per acre in

vegetable production after subtracting all operating expenses.

TABLE 6. VEGETABLE ENTERPRISE LABOR PAYROLL TO REVENUE RATIO

Scale

Percentile

10 25 median 75 90

< 3 acres 0% 3% 12% 19% 70%

3–12 acres 11% 19% 26% 31% 53%

> 12 acres 32% 32% 33% 33% 35%

= 100% * paid labor for vegetable enterprise / gross vegetable enterprise revenue

Vegetable enterprise labor payroll to revenue ratio shows the cost of

paid labor associated with a vegetable enterprise relative to gross vegetable

enterprise revenue. It does not include wages or salaries paid to farm owners,

family members, or business partners.

On some smaller-scale farms, where the farm owner(s) and their family

account for all labor, this ratio can be zero. On larger farms with many paid

employees,laborcostscanbeasignicantpercentageofrevenue.

PASA SUSTAINABLE AGRICULTURE | 13

TABLE 7. VEGETABLE ENTERPRISE NET INCOME TO REVENUE RATIO

Scale

Percentile

10 25 median 75 90

< 3 acres -12% -4% 3% 12% 15%

3–12 acres -87% -6% 14% 22% 38%

> 12 acres 9% 9% 14% 26% 34%

= 100% * (gross vegetable enterprise revenue – vegetable enterprise operating expenses /

gross vegetable enterprise revenue

Vegetable enterprise net income to revenue ratio shows vegetable enterprise

net income as a percentage of gross vegetable enterprise revenue. This ratio can

provideinsightintotheprotpotentialandviabilityofavegetableenterprise.

Becauseourdenitionofoperatingcostsdoesnotincludecompensationfor

farm owners, other family members, or business partners, a vegetable enterprise

isprobablynotnanciallyviableifthisindicatorisconsistentlylessthanzero,

or only slightly above zero. By contrast, ratios well above 20% are probably

necessary for most farms to be in a position to compensate farm owners.

Before [this study], we had no basis for comparison

to help determine if we were fairly successful relative

to other farms, as well as how much is reasonable

to expect to make from other similarly sized farm

businesses.

—Study participant

“

14 | FINANCIAL BENCHMARKS FOR DIRECT-MARKET VEGETABLE FARMS

TABLE 8. VEGETABLE ENTERPRISE RATE OF RETURN ON FARM OWNER LABOR

Scale

Percentile

10 25 median 75 90

< 3 acres -$45,956 -$278 $1,462 $2,273 $5,135

3–12 acres -$60,109 -$2,101 $9,819 $16,770 $31,882

> 12 acres $19,840 $20,307 $34,319 $49,248 $56,039

= 100% * (gross vegetable enterprise revenue – vegetable enterprise operating expenses) /

FTEs farm owner labor for vegetable enterprise

Vegetable enterprise rate of return on farm owner laborshowsthenancial

returns of the labor a farm owner(s), other family members, and business

partners contributed to a vegetable enterprise. It is the ratio of the net income

from vegetables to the total farm owner labor on the farm, expressed in full

time equivalents (FTEs) of 2,000 hours per year.

Most farmers work much more than 2,000 hours per year (~38.5 per week)—

half of farmers participating in our study worked more than 45 hours per week

on average, and 25% worked more than 55 hours per week on average. We

standardized the farm owner input in terms of a 2,000 hour annual FTE, such

that a farmer who works 55 hours per week on average would be represented

as ~1.4 FTE.

To put this indicator into context, a vegetable enterprise rate of return on

farm owner labor of $20,000 indicates that each farm owner is earning about

$10 per hour while working on the vegetable enterprise.

[This study] prompted us to take a closer look at our

nances, which is never time wasted. And it’s really

helpful to know how we compare to other farms in

terms of expenses and revenue generated per acre.

—Study participant

“

PASA SUSTAINABLE AGRICULTURE | 15

FARM BUSINESS BENCHMARKS

The benchmarks in this section apply to all enterprises on a farm combined.

TABLE 9. GROSS FARM BUSINESS REVENUE

Scale

Percentile

10 25 median 75 90

< 3 acres $17, 587 $72,259 $80,623 $133,046 $193,922

3–12 acres $62,661 $82,964 $111,876 $216,734 $290,681

> 12 acres $508,299 $579,144 $773,046 $1,158,227 $1,366,547

Gross farm business revenue shows the overall economic scale of a farm

business. As mentioned above, this includes a farm’s vegetable enterprise as

well as all other revenue gained from other farm enterprises. This may include

revenue sources such as eggs, dairy products, meat, agritourism, custom

services, or resold products.

TABLE 10. PERCENT FARM BUSINESS REVENUE FROM VEGETABLE ENTERPRISE

Scale

Percentile

10 25 median 75 90

< 3 acres 55% 60% 75% 86% 98%

3–12 acres 34% 56% 80% 98% 100%

> 12 acres 37% 51% 87% 95% 98%

= 100% * gross vegetable enterprise revenue / gross farm business revenue

Percent farm business revenue from vegetable enterprise shows the

degree to which a farm specializes in vegetable production. It shows a farm’s

gross vegetable enterprise revenue (Table 2) as a percentage of the gross farm

business revenue ( Table 9).

16 | FINANCIAL BENCHMARKS FOR DIRECT-MARKET VEGETABLE FARMS

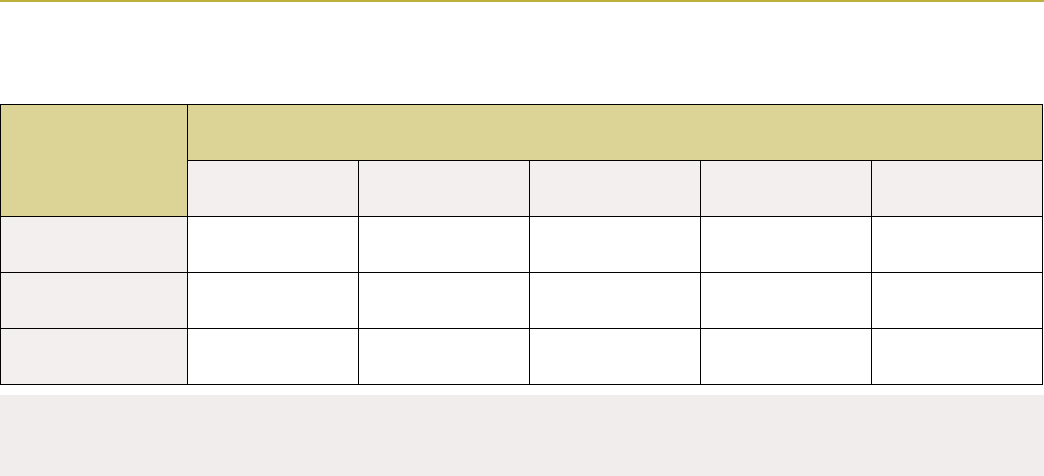

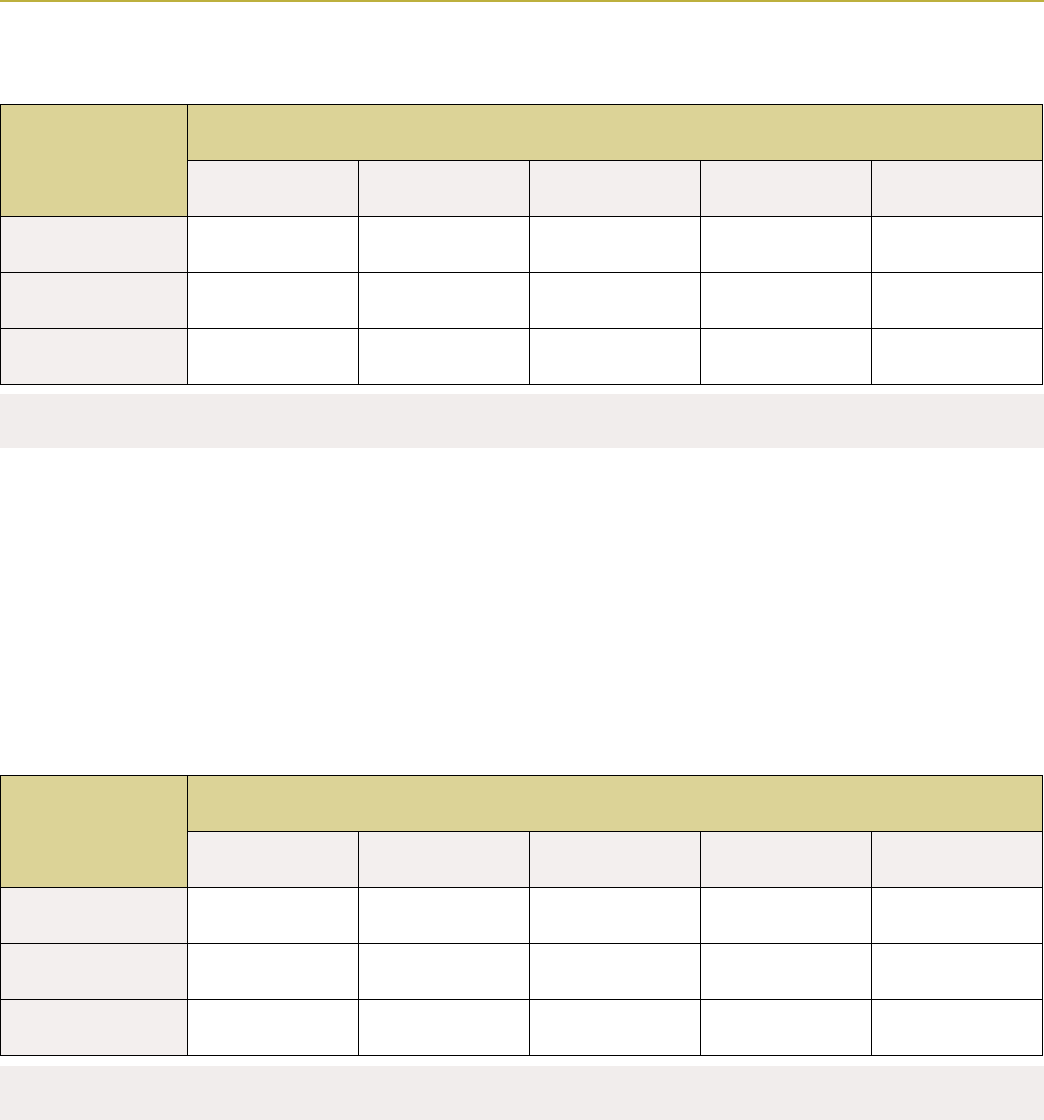

TABLE 11. FARM BUSINESS NET INCOME

Scale

Percentile

10 25 median 75 90

< 3 acres -$9,536 $2,968 $5,791 $13,577 $21,186

3–12 acres -$8,266 $9,915 $29,907 $52,145 $65,048

> 12 acres -$12,134 $48,915 $81,151 $162,695 $228,083

= gross farm business revenue – farm business operating expenses

Farm business net income shows the total income

generated by a farm business that is available to

compensate farm owners or make capital investments

in the operation.

Ourdenitionofoperatingexpensesincludes

all farm production and marketing costs, including

paid labor, land rental costs, and mortgage interest

payments. Farm business operating expenses may also

include the cost of goods sold for resale products.

Ourdenitionofoperatingexpensesdoesnotinclude

salaries for farm owners, other family members,

or business partners.

TABLE 12. FARM BUSINESS NET INCOME TO REVENUE RATIO

Scale

Percentile

10 25 median 75 90

< 3 acres -7% 3% 9% 17% 19%

3–12 acres -16% 11% 18% 35% 45%

> 12 acres 1% 8% 11% 17% 26%

= 100% * (gross farm business revenue – farm business operating expenses) / gross farm business revenue

Farm business net income to revenue ratio shows the

farm business net income (Table 11) as a percentage of

the gross farm business revenue (Table 9). It provides

insightintotheprotpotentialandviabilityofafarm

business.Becauseourdenitionofoperatingcosts

does not include compensation for farm owners, other

family members, or business partners, a farm business

isprobablynotnanciallyviableifthisindicatoris

consistently less than zero, or only slightly above

zero. By contrast, ratios well above 20% are probably

necessary for most farms to be in a position

to compensate farm owners.

PASA SUSTAINABLE AGRICULTURE | 17

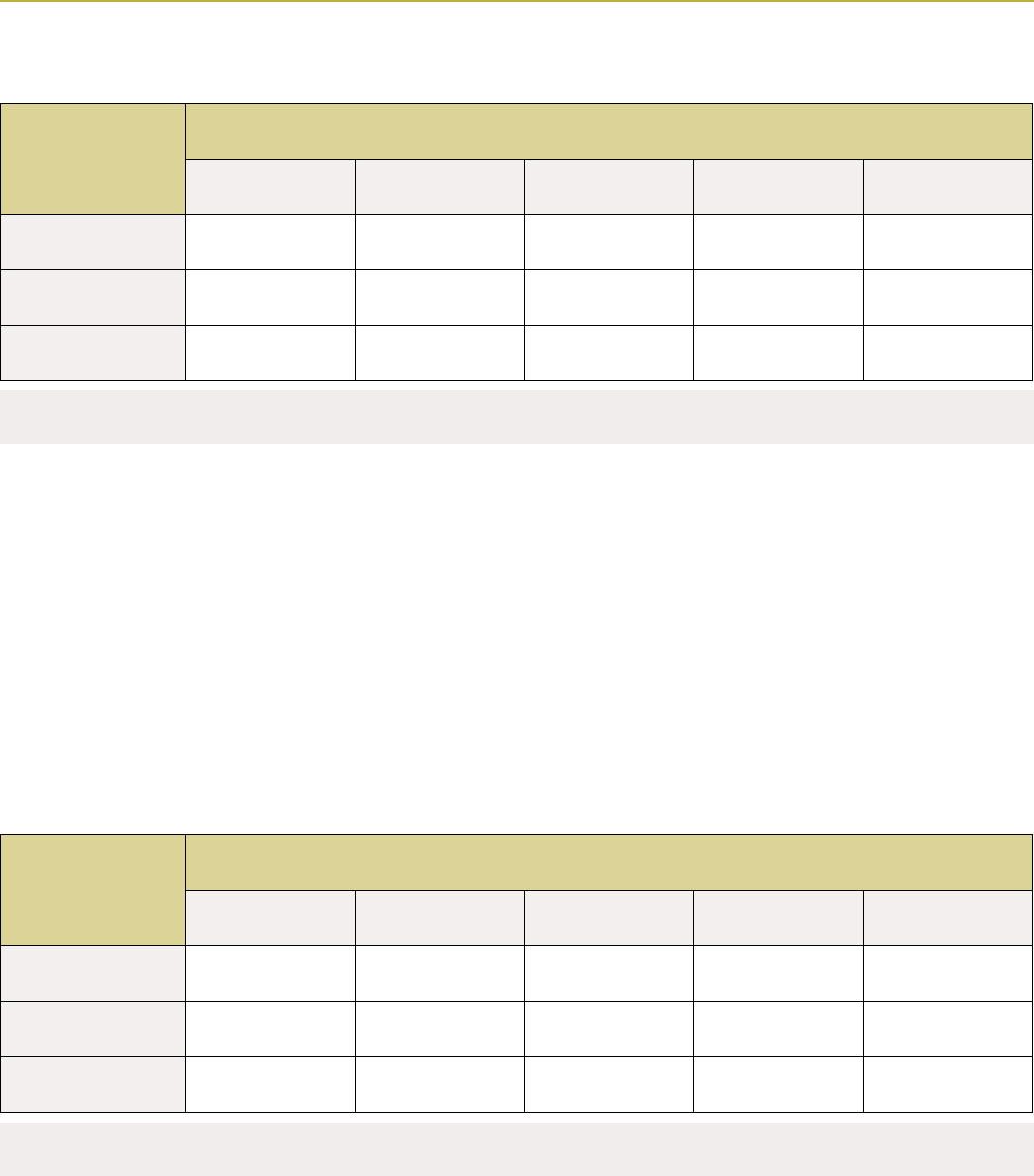

TABLE 13. FARM BUSINESS RATE OF RETURN ON FARM OWNER LABOR

Scale

Percentile

10 25 median 75 90

< 3 acres -$9,777 $1,484 $3,826 $6,692 $11,885

3–12 acres -$8,217 $7, 8 0 0 $14,990 $19,130 $39,986

> 12 acres -$31,984 $18,917 $26,937 $54,935 $68,411

= (gross farm business revenue – farm business operating expenses) / FTEs farm business labor

Farm business rate of return on farm owner labor

showsthenancialreturnsofallofthelaborfarm

owners, other family members, and business partners

contributed to the farm business. It is the ratio of

the farm business net income (Table 11) to the total

farm owner labor on the farm, expressed in full-time

equivalents (FTEs) of 2,000 hours per year.

While most farmers work much more than full

time—half of farmers participating in our study worked

more than 45 hours per week on average, and 25%

worked more than 55 hours per week on average—we

standardized farm owner labor in terms of a 2,000 hour

annual FTE (~38.5 hours per week).

To put this indicator into context, a farm business

rate of return on farm owner labor of $20,000

indicates that each farm owner is earning about $10 per

hour while working on the farm business.

TABLE 14. FARM BUSINESS DEBT-TO-ASSET RATIO

Scale

Percentile

10 25 median 75 90

< 3 acres 0% 0% 6% 49% 79%

3–12 acres 0% 1% 18% 46% 67%

> 12 acres 5% 13% 25% 50% 61%

= 100% * farm business debts / farm business assets

Farm business debt-to-asset ratio is a measurement

of a farm’s overall solvency. It shows the proportion of

assetsthatarenancedbyloansversusinvestments

from a farm family and business partners. This indicator

is the ratio of the remaining principal on debts owed by

a farm business (including mortgage debt for farmland,

loans for equipment purchases, and operating loans)

to the estimated market value of the farm’s business

assets (including farmland, buildings, equipment,

and inventory).

18 | FINANCIAL BENCHMARKS FOR DIRECT-MARKET VEGETABLE FARMS

Insights

MOST DIRECT-MARKET VEGETABLE FARMERS

ARE NOT EARNING A MIDDLE–CLASS INCOME

Some direct-market vegetable farmers have reached various degrees

ofnancialstability.Most,however,aren’tearningamiddle-classincome—

or even a living wage.

A quarter of farms are earning net incomes greater than the Pennsylvania

median household income of $56,951. For most, though, the median net farm

business income of $18,549 is substantially less than the Pennsylvania median

household income. For context, the statewide poverty rate in Pennsylvania for

a two-person household is $17,420.

4

Additionally, 71% of participating farms had net farm business incomes

less than the average Pennsylvania farm income of $42,875. Notably, however,

roughly 55% of all Pennsylvania farms operated at a net loss in 2017 (the date

of the most recent Census of Agriculture), while 82% of the vegetable farms

in our study showed positive incomes each year.

5

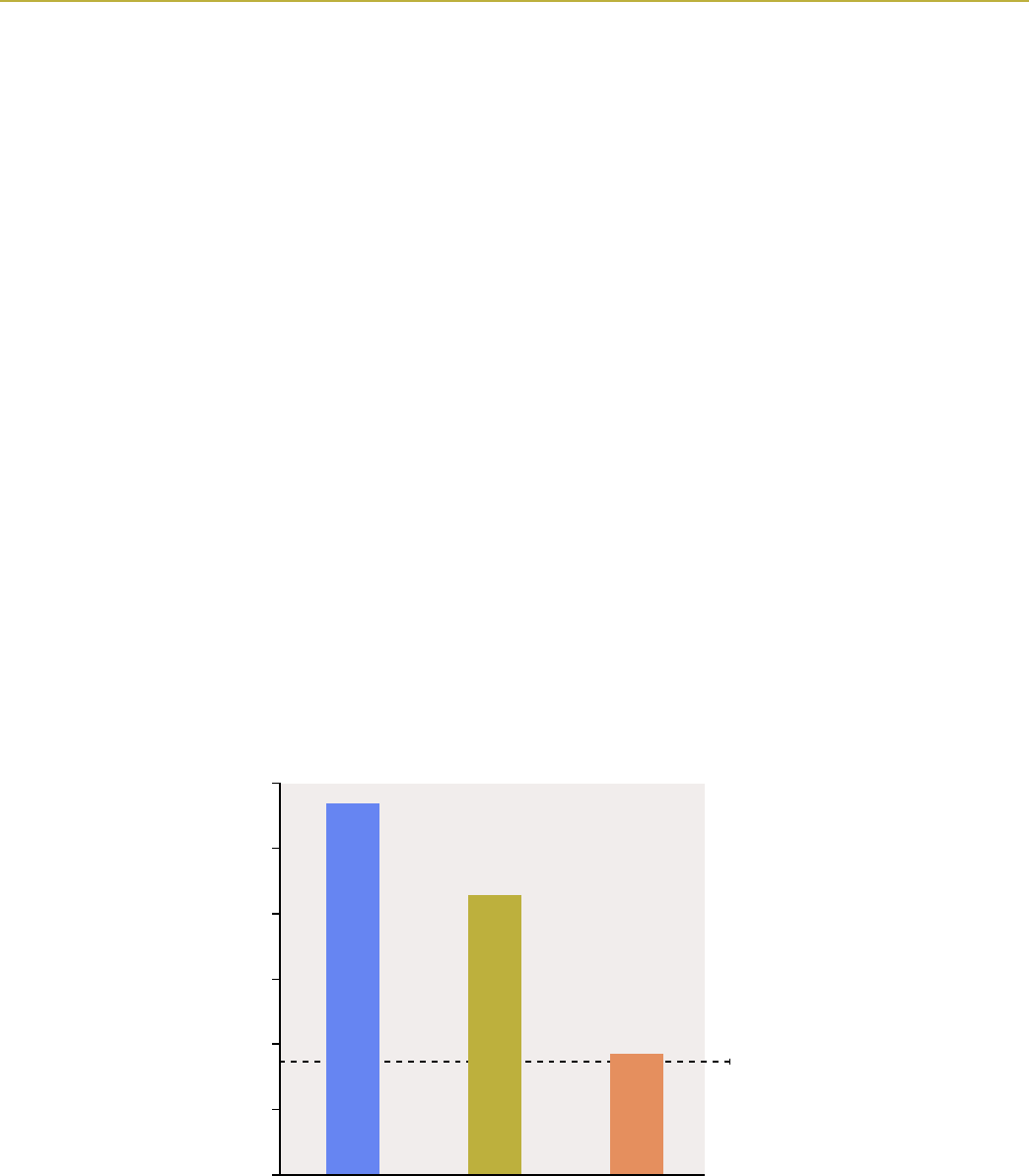

FIGURE 4. MEDIAN NET INCOMES FOR PA

HOUSEHOLDS, FARMS & STUDY PARTICIPANTS

Median net incomes, $1,000s

0 10 3020 40 50

All PA households

60

All PA farms Study participants

PA poverty line

PASA SUSTAINABLE AGRICULTURE | 19

Direct-market vegetable farms typically utilize a variety

of sales channels, including farmers markets; CSA

programs; direct wholesale to restaurants, grocery

stores, and institutions; and other direct markets

including on-farm and online stores. Some direct-

market farms also use wholesale-to-intermediary

channels such as produce auctions, food service

companies, and marketing co-ops. Are some of these

marketchannelsconsistentlymoreprotablethan

others?

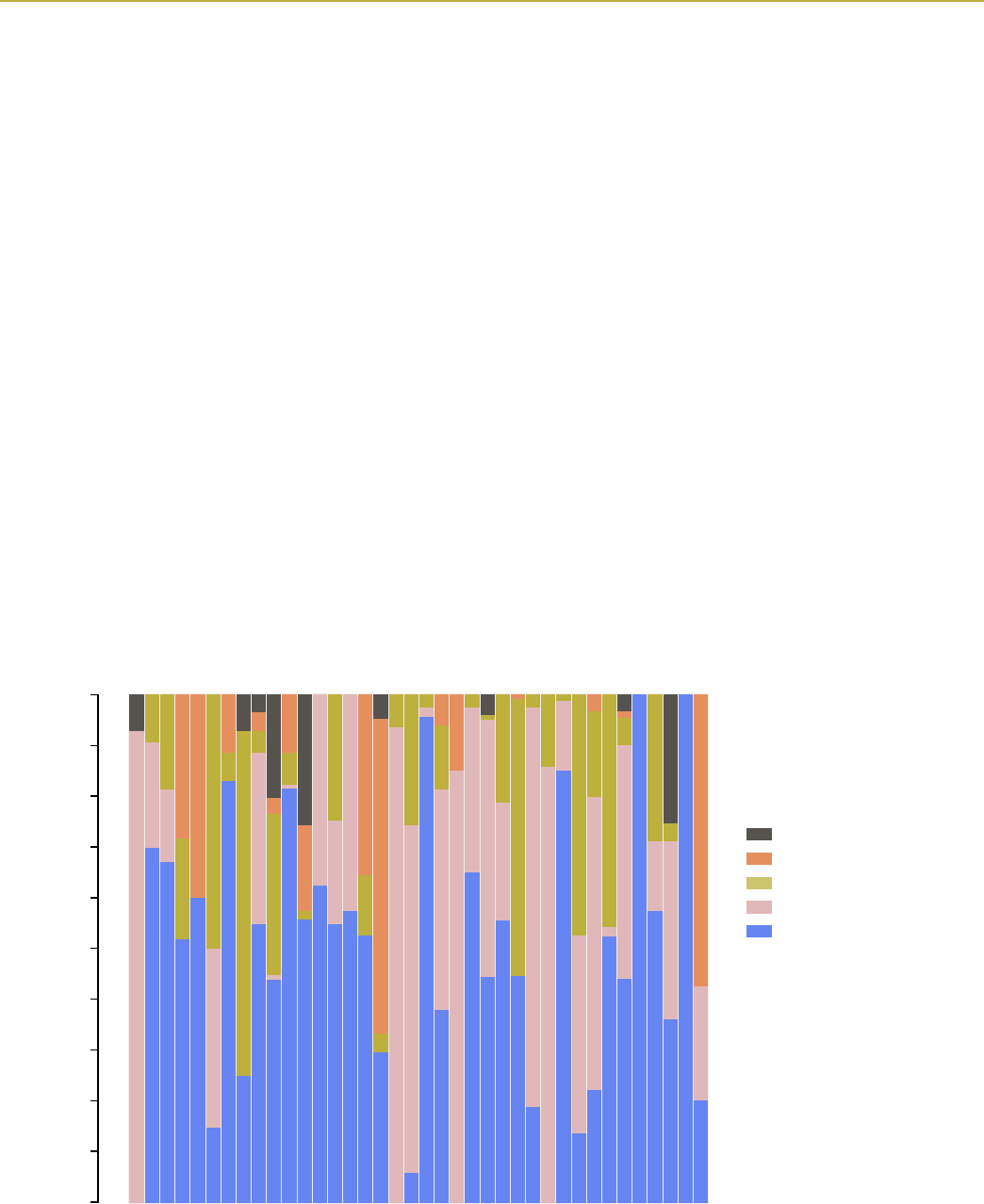

Figure 5 shows each participating farm’s gross

vegetable enterprise revenue (Table 2), allocated by

its percentage of sales through CSAs, farmers markets,

direct wholesale, other direct markets (often on-farm

and online stores), and wholesale to intermediaries.

Eachfarmisrankedbyprotability,asmeasuredby

their vegetable enterprise net income to revenue

ratio (Table 7).

The chart suggests that no single direct-market

channelisconsistentlymoreprotablethanothers.We

foundprotablefarmsusingamixofmarketchannels.

Wealsofoundprotablefarmsprimarilyfocusedon

selling their products through CSAs or farmers markets.

Conversely,wealsofoundlessprotablefarmsusing

amixofmarketchannels,andlessprotablefarms

focused on single market channels. For context, the

mostprotablevegetableenterpriseinourstudyhad

an average net income of $192,525 while the least

protablevegetableenterprisehadanaveragenet

income of -$42,408.

Vegetable enterprises ranked by net income

NO SINGLE DIRECT-MARKET CHANNEL

OUTPERFORMED ALL OTHERS

FIGURE 5. NET VEGETABLE ENTERPRISE INCOME & MARKET CHANNEL COMPOSITION

Data are the mean values for each

farm, averaged for all years over

2017–19 for which we have data for

that farm.

% Intermediary wholesale

% Other direct markets

% Direct wholesale

% Farmers markets

% CSA

Vegetable enterprises gross revenues,

% by market channel

0 10 10020 30 40 50 60 70 80 90

MostprotableLeastprotable

20 | FINANCIAL BENCHMARKS FOR DIRECT-MARKET VEGETABLE FARMS

Data are the mean values for each farm, averaged for all years over 2017–19 for which we have data for that farm.

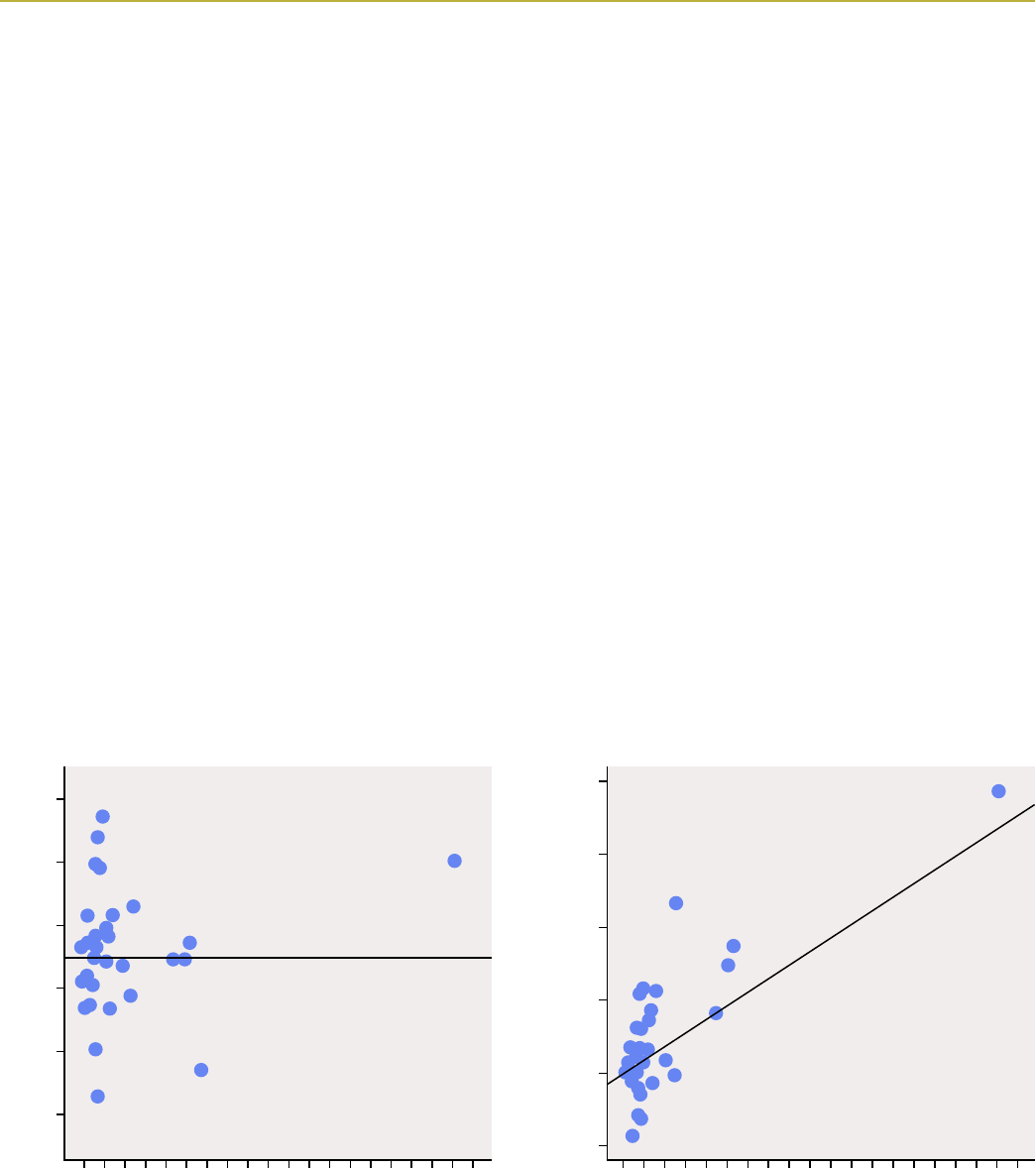

Farms in our study were growing vegetables across

a wide range of scales, from approximately half an

acre to 90 acres (with a median of four acres). To

explorerelationshipsbetweenscaleandprot,we

reviewed both the vegetable enterprise net income

to revenue ratio (Table 7), which measures the

proportion of revenue that farmers are able to keep,

and the vegetable enterprise net income (Table 4),

which measures the net amount that farmers earn from

vegetables.

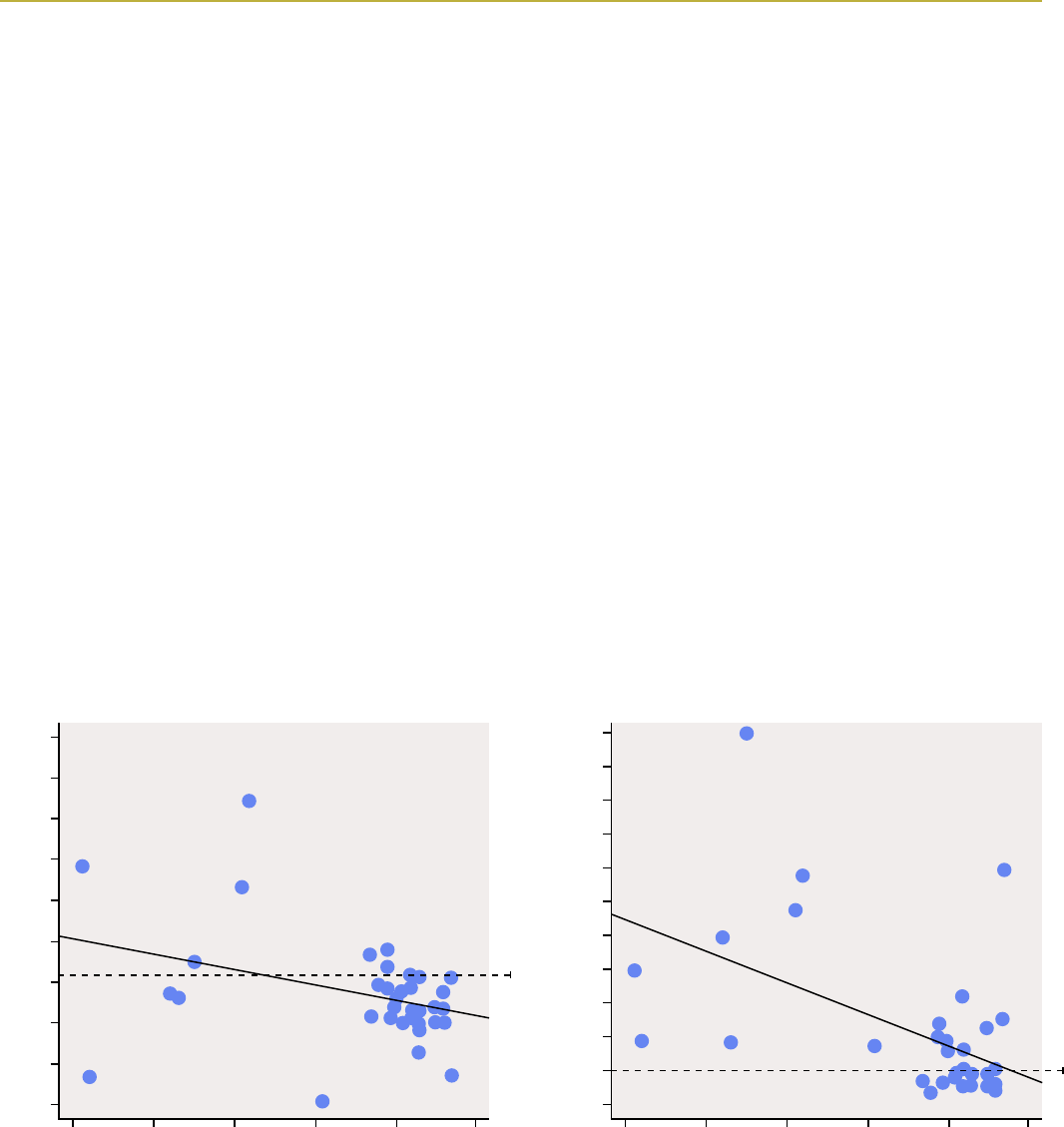

We did not see a consistent correlation between

the number of acres in vegetable production and the

vegetable enterprise net income to revenue ratio

(Figure 6A). While there is considerable variation across

the median (the horizontal line), the lack of a clear

correlation suggests that farmers can achieve similar

protmarginsacrossarangeofproductionscales.

In other words, smaller farmers are not consistently

moreorless“efcient”atearningincomethanlarger

farmers.

At the same time, there is a clear correlation

between the number of vegetable acres in production

and vegetable enterprise net income (Figure 6B).

Although there is also considerable variation in this

pattern, the trend line suggests that for larger farms,

the farm owners and business partners are able to draw

larger incomes from their vegetable enterprises. While

scaling up acres in vegetable production is rarely easy

and not always desirable, these data do suggest that

bigger scales can lead to higher incomes for farmers.

FIGURE 6A. VEGETABLE ENTERPRISE NET INCOME

TO REVENUE RATIO RELATED TO ACRES IN

VEGETABLE PRODUCTION

Veg enterprise net income to revenue ratio, %

Acres in vegetable production

-40 -20 200 40 60

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90

FIGURE 6B. VEGETABLE ENTERPRISE NET INCOME

RELATED TO ACRES IN VEGETABLE PRODUCTION

Veg enterprise net income, $1,000s

Acres in vegetable production

0 10050 150 200

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90

-50

LARGER PRODUCTION SCALES BRING HIGHER INCOMES

PASA SUSTAINABLE AGRICULTURE | 21

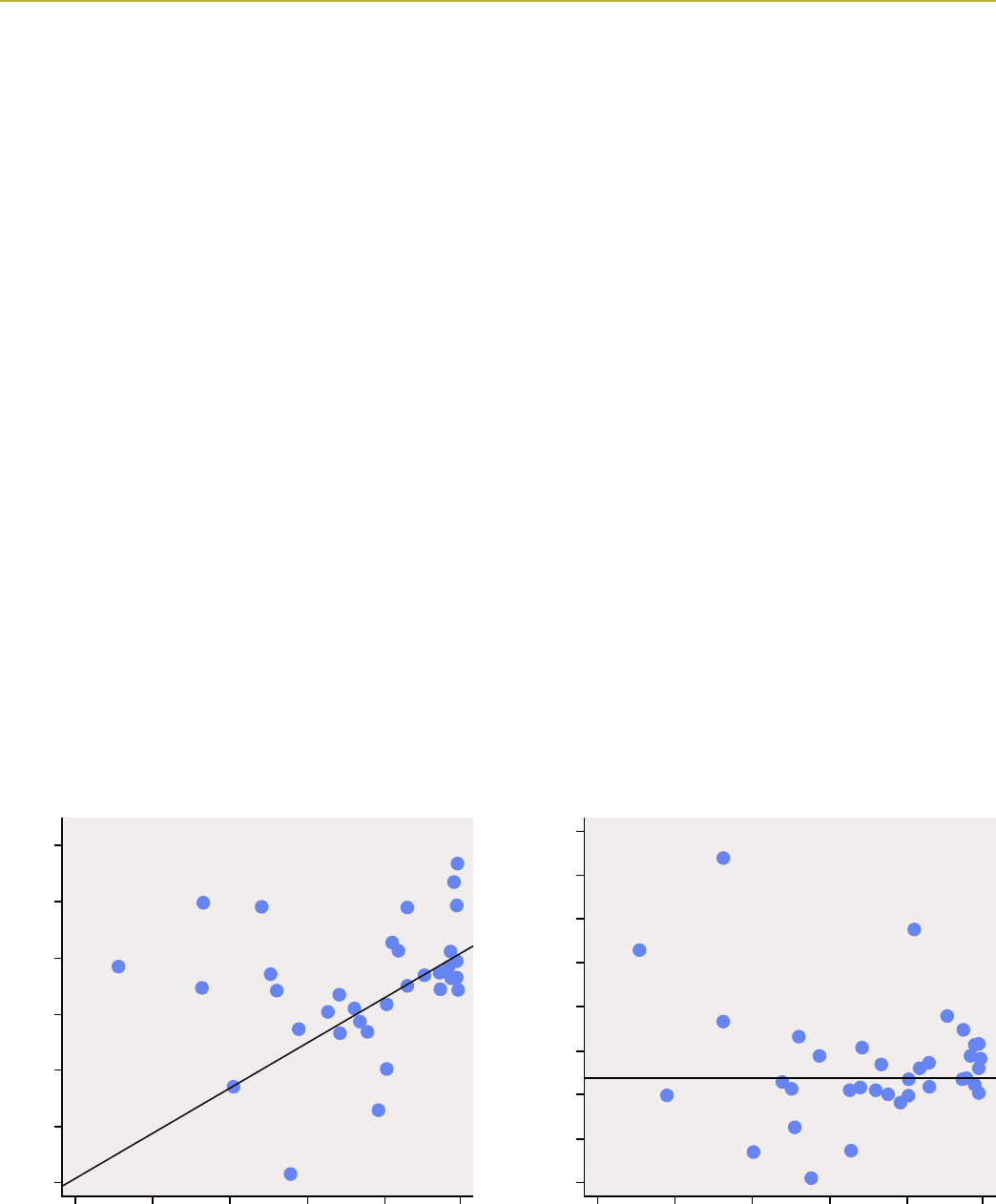

Do farms that primarily focus on growing vegetables

make more or less money than farms that diversify into

other enterprises? Based on the vegetable enterprise

net income to revenue ratio (Table 7), we found

that farms with a high degree of focus in vegetable

productiontendedtobemoreprotableintheir

vegetable enterprise (Figure 7A).

Althoughwefoundsignicantvariation,farmswith

90% or more of their revenue coming from vegetables

grown on their farm showed some of the highest

vegetable enterprise net income to revenue ratios

in our cohort. This trend suggests that farmers who

focusongrowingvegetablescanbuildefcienciesin

their operations that farm businesses with more diverse

revenue streams may be less likely to develop.

At the same time, we found several examples of

protablefarmsthatearnedasignicantpercentageof

their revenue through enterprises other than vegetables

(Figure 7B). While the relationship is not statistically

signicant,someofthemostprotablefarmsinour

study made more than 20% of their revenue from other

enterprises. The most common enterprise other than

vegetables in our cohort was reselling products grown

or raised on other local farms.

This suggests that reselling can be a valuable

strategy for increasing farm business net income

(Table 11). By offering a greater range of livestock

products, fruit, and vegetables grown or raised on

other local and sustainable farms, reselling can help

attract and retain customers. Collaborating with

partnerfarmsthataremoreefcientproducersof

supplementary products can also often help farmers

capture a higher margin with resale items than

comparable items grown on their own farm.

Otherprotableenterprisesamongparticipating

farms included nursery and ornamental plants; on-farm

events and agritourism; and pastured livestock,

including sheep, pigs, and poultry.

Data are the mean values for each farm, averaged for all years over 2017–19 for which we have data for that farm.

FIGURE 7A. VEGETABLE ENTERPRISE NET INCOME

TO REVENUE RATIO RELATED TO CONCENTRATION

IN VEGETABLE ENTERPRISE

Veg enterprise net income to revenue ratio, %

% Farm business revenues from veg enterprise

0 20 40 60 80 100

-40 0-20 40 60-60 20

FIGURE 7B. FARM BUSINESS NET INCOME RELATED

TO CONCENTRATION IN VEGETABLE ENTERPRISE

Farm business net income, $1,000s

% Farm business revenues from veg enterprise

-50 500 100 150-100

0 20 40 60 80 100

200 250 300

FARMS THAT FOCUS ON VEGETABLES MAKE MORE MONEY ON VEGETABLES—

BUT MAY MISS OUT ON HIGHER NET INCOMES FROM OTHER ENTERPRISES

22 | FINANCIAL BENCHMARKS FOR DIRECT-MARKET VEGETABLE FARMS

Farmers in our study possessed a wide range of

vegetable production and business management

experience. The newest participating farm started in

2017, while other businesses in our study had existed

for more than 40 years.

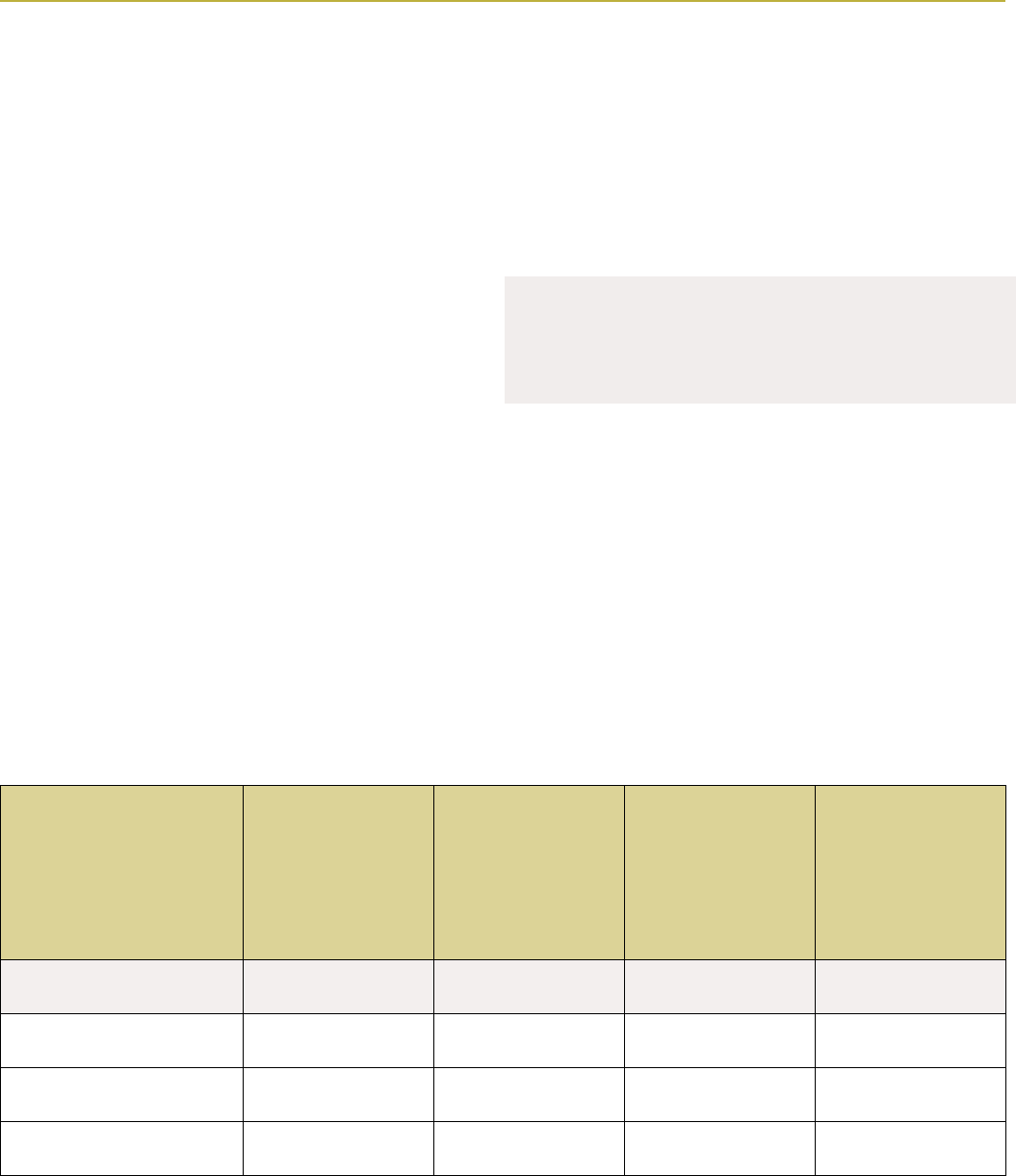

For the farm business as a whole, there is a clear

relationship between a farm’s number of years in

business and its farm business net income ( Table

11). In Figure 8A we can see that although there is

considerable variation, the trend line in solid black

suggests that it can take approximately 10 years for a

farm business to achieve a farm business net income

equal to the 2017 Pennsylvania median household

income of $56,951, represented by the dotted line.

We also found a clear pattern between the number

of years a farm was in business and its farm business

equity, which is a farm’s total value of assets minus

its debts, as shown in Figure 8B. Many farmers build

considerable equity in their business as they continue

farming—most farms that had been in business for 10

or more years had considerably more equity in their

business than the median 2017 Pennsylvania household

net worth of $105,594 (represented by the dotted line).

Data are the mean values for each farm, averaged for all years over 2017–19 for which we have data for that farm.

FARMS STEADILY INCREASED INCOME AND EQUITY OVER TIME

FIGURE 8A. FARM BUSINESS NET INCOME RELATED

TO NUMBER OF YEARS IN BUSINESS

Farm business net income, $1,000s

Farm business start year

1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 2020

-50 500 150 200-100 100 250 300 350

2017 PA median household income

FIGURE 8B. FARM BUSINESS EQUITY RELATED

TO NUMBER OF YEARS IN BUSINESS

Farm business equity, $1,000s

Farm business start year

300 1,100700 1,500 1,900-100

1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 2020

2017 PA household net worth

PASA SUSTAINABLE AGRICULTURE | 23

Trends: 2017–19

A subset of 19 farms participated in our study over three years between 2017

and 2019. By monitoring these farms over multiple years, we’re offered a unique

look at how farm business outcomes might change over time.

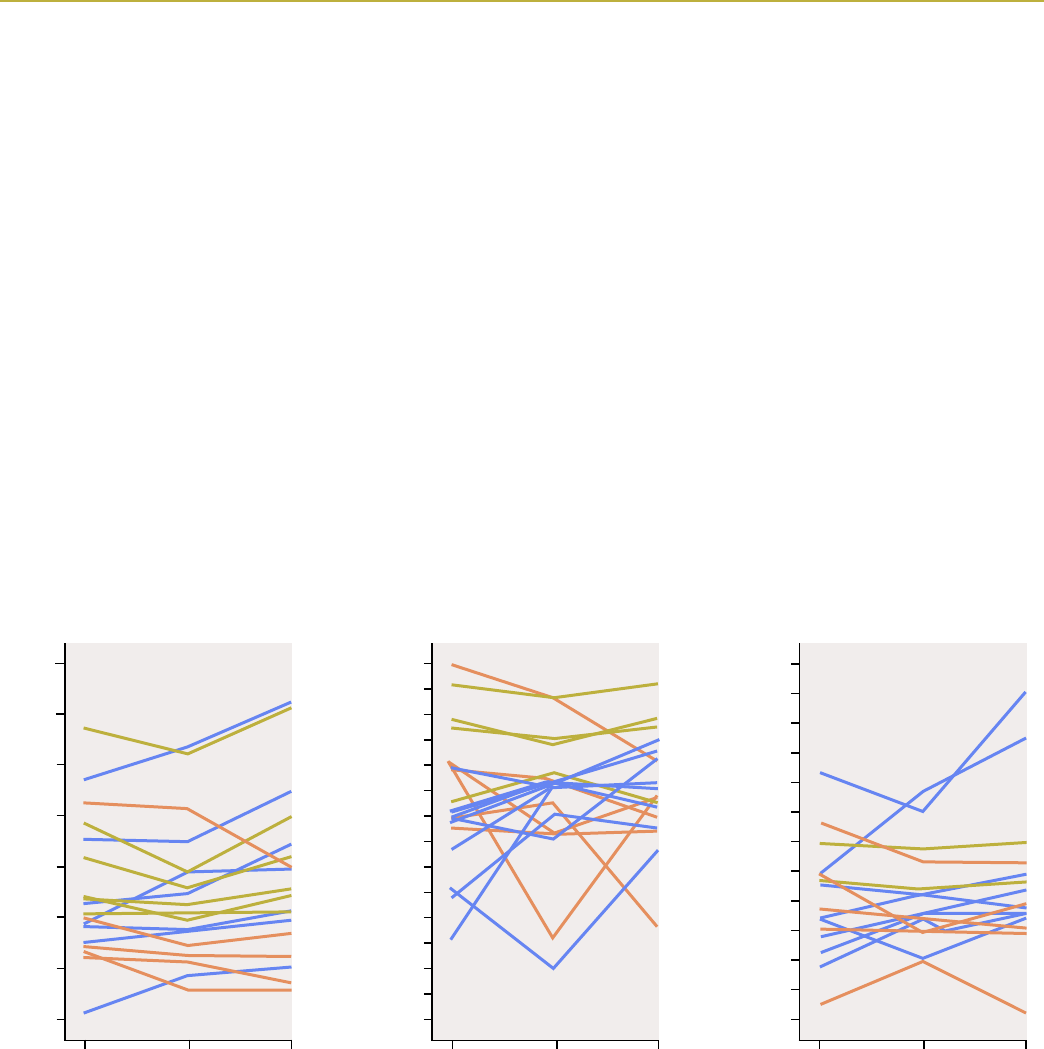

In Figures 9A–C we show year-to-year trends for three key indicators: gross

vegetable enterprise revenue per acre (Table 3), vegetable enterprise

income to revenue ratio (Table 7), and vegetable enterprise net income

(Table 4). These data suggest that most farms improved or maintained their

nancesoverthethreeyearstheyparticipatedinourstudy.

For each indicator, each line represents an individual farm.

Blue line: Farm that showed a 10% or greater increase

Orange line: Farm that showed at least a 10% decrease

Green line: Farm with little change

FIGURE 9B. VEGETABLE

ENTERPRISE NET INCOME

TO REVENUE RATIO,

2017–19

Veg net income to revenue ratio, %

2017 2018 2019

-70 -50 -10-30 10 30

50

70

Gross veg enterprise revenues per acre, $1,000s

2017 2018 2019

0 10 3020 40 50

60

70

FIGURE 9A. TRENDS

IN GROSS VEGETABLE

ENTERPRISE REVENUE

PER ACRE, 2017–19

Veg net income, $1,000s

2017 2018 2019

-60 -20 6020 100 140

180

FIGURE 9C. VEGETABLE

ENTERPRISE NET

INCOME, 2017–2019

24 | FINANCIAL BENCHMARKS FOR DIRECT-MARKET VEGETABLE FARMS

As shown in Figure 9A, seven of the 19 farms increased their gross

vegetable enterprise revenue per acre by more than 10% over three years,

while six roughly stayed the same.

Trends in vegetable enterprise net income to revenue ratio, as shown

in Figure 9B, were more variable. Two farms showed very pronounced dips in

2018, but by 2019 one of these had achieved a net increase while the other

recovered to a more modest loss. By 2019, nine had substantially increased

their ratio, while six had decreases of 10% or more relative to 2017.

As shown in Figure 9C, 12 out of 19 farms increased their vegetable

enterprise net income by more than 10% while two stayed roughly the same.

One farm with more than 12 acres in vegetable production increased its net

income by more than $92,000 over this period, achieved by simultaneously

expanding its vegetable acres in production; improving its equipment and

infrastructure;andfulllinglargewholesalecontractstointermediaries.

The 2018 season was exceptionally notable for the severe weather in the

Mid-Atlantic region, especially during the late summer and fall months. Annual

precipitation was 50% above average in much of the region, leading to many

countiesbeingdeclaredfederaldisasterareasduetopersistentoods.Many

farmers in our study reported major drops in yields and even abandoned some

fall crops.

Fortunately, despite these setbacks, our data suggest that these farms’

business models were resilient against disastrous weather. Most farms

maintained consistent net incomes in 2018, while some even improved their

net incomes. Anecdotally, many farms reported that their CSA programs were

critical to this resilience—prepaid spring CSA revenue allowed them to maintain

cashowdespiteloweryields.In2019,mostoftheirCSAcustomersreturnedto

enjoy renewed availability and diversity of produce in their subscriptions.

The 2018 season was exceptionally notable for the severe

weather in the Mid-Atlantic region, especially during the

late summer and fall months. Fortunately, despite these

setbacks, our data suggest that these farms’ business

models were resilient against disastrous weather. Most

farms maintained consistent net incomes in 2018, while

some even improved their net incomes.

“

PASA SUSTAINABLE AGRICULTURE | 25

income is the product of production scale, the value

ofvegetablesproducedperacre,andtheefciency

at which a farm can reduce costs and keep more of its

revenue as income.

Three pathways to higher incomes

For all three years of the study combined (2017-2019),

the median net farm business income (Table 11) for

all participating farms was $18,549, which is well below

the 2017 Pennsylvania median household income of

$56,951. In terms of return on farm owner labor

(Table 13), the median was only $11,684 per full-time

equivalent. While wealth accumulated in assets over

time adds a level of nuance (Figure 7B), most of the

farmers in our study worked long hours for very little

income.

These are sobering realities, but our study points

to several strategies that farmers can pursue to

improve their bottom lines. To demonstrate these

strategies, we created a simple exercise that compares

three different business models generating a net

vegetable enterprise income (Table 11) of $56,951—

the Pennsylvania median income. In each scenario,

Vegetable enterprise net income = vegetable acres

* gross vegetable enterprise revenue per acre *

vegetable enterprise net income to revenue ratio

The baseline scenario in our exercise shows a farm

with a vegetable enterprise net income currently at

$34,486 and assumes 2019 median values for vegetable

enterprise gross revenue per acre and the vegetable

enterprise net income to revenue ratio, for a farm with

10 acres in vegetable production. Table 15 demonstrates

three ways this farm might increase its income.

TABLE 15. SCENARIOS FOR ACHIEVING A NET INCOME GOAL ($56,951) FROM A VEGETABLE ENTERPRISE

BY INCREASING SCALE, INTENSITY, OR EFFICIENCY

Scenario

SCALE

(acres in

vegetable

production)

INTENSITY

(gross revenue

per acre in

vegetable

production)

EFFICIENCY

(vegetable

net income to

revenue ratio)

Vegetable

enterprise

net income

Baseline 10 $27,589 12.5% $34,486

1. Increase scale 16.5 $27,589 12.5% $56,951

2. Increase intensity 10 $45,561 12.5% $56,951

3. Increase efciency 10 $27,859 20.4% $56,951

26 | FINANCIAL BENCHMARKS FOR DIRECT-MARKET VEGETABLE FARMS

INCREASE SCALE

In scenario 1, we set net revenue per acre and the net income per revenue

ratioatthemedianstudyvaluesof$27,589and12.5%,respectively.Wend

that the farm in this example would need to increase the number of acres in

vegetable production from 10 to 16.5 to meet the net income target with this

business model.

However, if increasing the number of acres in vegetable production isn’t

possible—say, due to a limited amount of land available—a farmer might

consider the next two pathways toward higher income.

INCREASE INTENSITY

In scenario 2, our example farm focuses on increasing the amount of revenue it

earns in vegetables per acre. Perhaps the farm adjusts its crop plan to focus on

growing higher value crops with quicker rotations.

By increasing its gross vegetable enterprise revenue per acre from

$27,589 to $45,561, our example farm can meet its income goal. In fact, in

2019, 13% of farms in our study realized a gross revenue per acre in vegetable

production above $45,000, illustrating that this strategy can be feasible with

the right mix of crops and market channels.

INCREASE EFFICIENCY

Inscenario3,ourexamplefarmworkstoincreaseitscostefciency,perhaps

by controlling spending associated with payroll, supplies, and fuel. The farm

increases its vegetable net income to revenue ratio from 12.5% to 20.4%,

thereby reaching its income goal. In fact, in 2019, 30% of farms in our study

realized a ratio over 20%. Since payroll is typically among the biggest operating

expenses,improvinglaborefciencyandemployeemanagementskillsare

among the most important aspects of this business strategy.

PASA SUSTAINABLE AGRICULTURE | 27

Public support for

fair farm incomes

Of course, expanding scales, boosting revenue, and cutting costs are much

easier said than done. Only approximately 25% of farms in our study were able

to achieve net incomes at or above the median Pennsylvania household income

($56,951); most farms’ net incomes were less than half of this. The farmers

who did achieve higher incomes typically attributed their success to a mix of

hard work and good fortune—such as access to lucrative markets or reliable

farmland arrangements—that other farmers might not have.

Allofthefarmersparticipatinginourstudywanttooperateprotable,

self-sustainingbusinesses.Yetthesoberingnancialbenchmarkspresentedin

this report are consistent with persistent structural challenges in the agricultural

industry that negatively impact small- and medium-scale farms. Creating and

expanding public programs will be necessary to help direct-market vegetable

farmers continue their essential work providing fresh, nutritious food for their

communities. These programs should focus on equitably increasing farmland

access, improving market opportunities, encouraging workforce development,

reducingnancialrisk,andrewardingconservationbestpracticessuchas

building soil health, protecting wildlife, and improving water quality.

Only approximately 25% of farms in our study were able to

achieve net incomes at or above the median Pennsylvania

household income ($56,951); most farms’ net incomes were

less than half of this.

“

28 | FINANCIAL BENCHMARKS FOR DIRECT-MARKET VEGETABLE FARMS

Conclusion

This report shares a comprehensive and unique set of business benchmarks

for an important, growing sector of the agricultural landscape: direct-market,

diversiedvegetablefarms.Ourdatashowthatwhilesomefarmsparticipating

inourstudyhaveachievedarangeofdegreesofnancialstability,mostfarms

in this sector are earning incomes substantially below the household—and

farm—medians for Pennsylvania.

Ourdatashowthatsuccessfulfarmsutilizearangeofspecicdirect-market

channels—farmers markets, CSAs, on-farm stores, and direct wholesale—and

that no one channel clearly outperforms all others. We also found that income

andequitysteadilyincreasewithfarmerexperience,suggestingthatnancial

benchmarks may improve as farms in our cohort continue to evolve and mature.

Our study points to increasing production scale, revenue per acre, and labor

andcostefciencyaskeypathwaystoimprovingnetincomesamongdirect-

market vegetable farms. While entrepreneurial skill and grit are important,

it is also the case that sustainable, direct-market farmers are providing

valuable public services but retain little compensation from their efforts due

topersistentstructuralbarrierstoachievinglong-termnancialviabilityin

the agriculture industry. New and expanded public programs for equitably

increasing farmland access, improving market opportunities, encouraging

workforcedevelopment,reducingnancialrisk,andrewardingconservation

best practices are needed for these farms to thrive.

The power of this study is that participating farms can more clearly see

therangeofnancialpossibilitiesfortheirbusinessesandconnectwithother

farmers who are navigating similar challenges. Without these data, farmers

areunabletoknowiftheirfarms’nancesarenormaloratypical,andtheyare

unable to gauge if plans for the future may be achievable or unreasonable.

We hope this report offers farmers, farmer organizations, policymakers, and

communitiesvaluableinsightsthatcanbedrawnfromtoimprovenancial

outcomes for direct-market vegetable farms.

Movingforward,wewillcontinuetocollectdirect-marketnancial

benchmarks with our growing cohort of Mid-Atlantic vegetable farmers. We

are also working with peer organizations in New England (Community Involved

in Sustainable Agriculture) and the Carolinas (Carolina Farm Stewardship

Association) to build new cohorts of direct-market vegetable farmers in other

regions. We also plan to use our data to provide a detailed look at how the

COVID-19 pandemic affected marketing, labor, and incomes on farms that have

participated in our study over multiple years.

PASA SUSTAINABLE AGRICULTURE | 29

We always welcome direct-market vegetable farms

to join our ongoing study. Participating farms receive

custom nancial benchmark reports and access to

a learning community of their peers.

Learn more at pasafarming.org/research or contact

us at research@pasafarming.org if you are interested

in joining.

30 | FINANCIAL BENCHMARKS FOR DIRECT-MARKET VEGETABLE FARMS

References

1. National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS) (2016). USDA Releases Results

of First Local Food Marketing Practices Survey.

https://www.nass.usda.gov/Newsroom/archive/2016/12_20_16.php

2. Kolbe, L. (2017). Whole Farm Financial Project Year 2 — An Analysis of 2014

Financials. Practical Farmers of Iowa, Ames. IA.

https://practicalfarmers.org/research/whole-farm-nancial-project-year-2-an-

analysis-of-2014-nancials/

3. Hendrickson, J. A. (2005). Grower to grower: Creating a livelihood on a fresh

market vegetable farm. Center for Integrated Agricultural Systems. Madison, WI.

https://cias.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/194/2008/07/grwr2grwr1.pdf

4. Pennsylvania Department of Human Services (2020). Federal Poverty Income

Guidelines for 2020, 50 Pa.B. 3672.

https://www.pacodeandbulletin.gov/Display/pabull?le=/secure/pabulletin/data/

vol50/50-29/951.html

5. National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS) (2019). Census of Agriculture —

2017 Census Full Report. Washington, DC.

https://www.nass.usda.gov/Publications/AgCensus/2017/index.php

PASA SUSTAINABLE AGRICULTURE | 31